Six years ago we put our daughter into a dual immersion Japanese program (in the United States) and it has changed some of my view of how we teach and learn languages, a process which is also affected by my slowly picking up conversational Welsh using the method at https://www.saysomethingin.com/ over the past year and change, a hobby which I wish I had more targeted time for.

Children learn language through a process of contextual use and osmosis which is much more difficult for adults. I’ve found that the slowly guided method used by SSiW is fairly close to this method, but is much more targeted. They’ll say a few words in the target language and give their English equivalents, then they’ll provide phrases and eventually sentences in English and give you a few seconds to form them into the target language with the expectation that you try to say at least something, or pause the program to do your best. It’s okay if you mess up even repeatedly, they’ll say the correct phrase/sentence two times after which you’ll repeat it again thus giving you three tries at it. They’ll also repeat bits from one lesson to the next, so you’ll eventually get it, the key is not to worry too much about perfection.

Things slowly build using this method, but in even about 10 thirty minute lessons, you’ll have a pretty strong grasp of fluent conversational Welsh equivalent to a year or two of college level coursework. Your work on this is best supplemented with interacting with native speakers and/or watching television or reading in the target language as much as you’re able to.

For those who haven’t experienced it before I’d recommend trying out the method at https://www.saysomethingin.com/welsh/course1/intro to hear it firsthand.

The experience will give your brain a heavy work out and you’ll feel mentally tired after thirty minutes of work, but it does seem to be incredibly effective. A side benefit is that over time you’ll also build up a “gut feeling” about what to say and how without realizing it. This is something that’s incredibly hard to get in most university-based or book-based language courses.

This method will give you quicker grammar acquisition and you’ll speak more like a native, but your vocabulary acquisition will tend to be slower and you don’t get any writing or spelling practice. This can be offset with targeted memory techniques and spaced repetition/flashcards or apps like Duolingo that may help supplement one’s work.

I like some of the suggestions made in Lynne Kelly’s post about Chinese as I’ve been pecking away at bits of Japanese over time myself. There’s definitely an interesting structure to what’s going on, especially with respect to the kana and there are many similarities to what is happening in Japanese to the Chinese that she’s studying. I’m also approaching it from a more traditional university/book-based perspective, but if folks have seen or heard of a SSiW repetition method, I’d love to hear about it.

Hopefully helpful by comparison, I’ll mention a few resources I’ve found for Japanese that I’ve researched on setting out a similar path that Lynne seems to be moving.

Japanese has two different, but related alphabets and using an app like Duolingo with regular practice over less than a week will give one enough experience that trying to use traditional memory techniques may end up wasting more time than saving, especially if one expects to be practicing regularly in both the near and the long term. If you’re learning without the expectation of actively speaking, writing, or practicing the language from time to time, then wholesale mnemotechniques may be the easier path, but who really wants to learn a language like this?

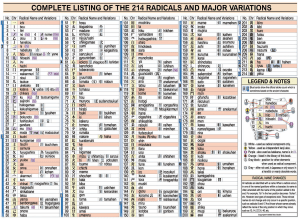

The tougher portion of Japanese may come in memorizing the thousands of kanji which can have subtly different meanings. It helps to know that there are a limited set of specific radicals with a reasonably delineable structure of increasing complexity of strokes and stroke order.

The best visualization I’ve found for this fact is the Complete Listing of the 214 Radicals and Major Variations from An Introduction to Japanese Kanji Calligraphy by Kunii Takezaki (Tuttle, 2005) which I copy below:

(Feel free to right click and view the image in another tab or download it and view it full size to see more detail.)

I’ve not seen such a chart in any of the dozens of other books I’ve come across. The numbered structure of increasing complexity of strokes here would certainly suggest an easier to build memory palace or songline.

I love this particular text as it provides an excellent overview of what is structurally happening in Japanese with lots of tidbits that are otherwise much harder won in reading other books.

There are many kanji books with various forms of what I would call very low level mnemonic aids. I’ve not found one written or structured by what I would consider a professional mnemonist. One of the best structured ones I’ve seen is A Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters by Kenneth G. Henshall (Tuttle, 1988). It’s got some great introductory material and then a numbered list of kanji which would suggest the creation of a quite long memory palace/journey/songline.

Each numbered Kanji has most of the relevant data and readings, but provides some description about how the kanji relates or links to other words of similar shapes/meanings and provides a mnemonic hint to make placing it in one’s palace a bit easier. Below is an example of the sixth which will give an idea as to the overall structure.

I haven’t gotten very far into it yet, but I’d found an online app called WaniKani for Japanese that has some mnemonic suggestions and built-in spaced repetition that looks incredibly promising for taking small radicals and building them up into more easily remembered complex kanji.

I suspect that there are likely similar sources for these couple of books and apps for Chinese that may help provide a logical overall structuring which will make it easier to apply or adapt one’s favorite mnemotechniques to make the bulk vocabulary memorization easier.

The last thing I’ll mention I’ve found, that’s good for practicing writing by hand as well as spaced repetition is a Kanji notebook frequently used by native Japanese speaking children as they’re learning the levels of kanji in each grade. It’s non-obvious to the English speaker, and took me a bit to puzzle out and track down a commercially printed one, even with a child in a classroom that was using a handmade version. The notebook (left to right and top to bottom) has sections for writing a big example of the learned kanji; spaces for the “Kun” and “On” readings; spaces for the number of strokes and the radical pieces; a section for writing out the stroke order as it builds up gradually; practice boxes for repeated practice of writing the whole kanji; examples of how to use the kanji in context; and finally space for the student to compose their own practice sentences using the new kanji.

Regular use and practice with these can be quite helpful for moving toward mastery.

I also can’t emphasize enough that regularly and actively watching, listening, reading, and speaking in the target language with materials that one finds interesting is incredibly valuable. As an example, one of the first things I did for Welsh was to find a streaming television and radio that I want to to watch/listen to on a regular basis has been helpful. Regular motivation and encouragement is key.

I won’t go into them in depth and will leave them to speak for themselves, but two of the more intriguing videos I’ve watched on language acquisition which resonate with some of my experiences are: