Tag: Zettelkasten

Typewriter Backing Sheets for Index Cards

Knowledge management practices on romantic display in George Eliot’s Middlemarch

In chapter two Mr. Brooke, the uncle, asks for advice about arranging notes as he has tried pigeon holes as a method but has the common issue of multiple storage and can’t remember under which letter he’s filed his particular note. [At the time, many academics would employ secretarial staff to copy their note cards multiple times so that a note that needed to be classified under “hope” and “liberty”, as an example, could be filed under both. Individuals working privately without the support of an amanuensis or additional indexing techniques would have had more difficulty with filing material in the same manner Mr Brooke did. Digital note takers using platforms like Obsidian or Logseq don’t have to worry about such issues now.]

Mr. Casaubon indicates that he uses pigeon-holes which was a popular method of filing, particularly in Britain where John Murray and the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary were using a similar method to build their dictionary at the time.

Our heroine Dorothea Brooke mentions that she knows how to properly index papers so that they might be searched for and found later. She is likely aware of John Locke’s indexing method from 1685 (or in English in 1706) and in the same passage—and almost the same breath—compares Mr. Casaubon’s appearance favorably to that of Locke as “one of the most distinguished-looking men I ever saw.”

In some sense here, we should be reading the budding romance, not just as one based on beautiful appearance or one’s station or even class, but one of intellectual stature and equality. One wants a mate not only as distinguished and handsome as Locke, but one with the beauty of mind as well. Without the subtextual understanding of knowledge management during this time period, this crucial component of the romance would be missed though Eliot later hints at it by many other means. Still, in the opening blushes of love, it is there on prominent display.

For those without their copies close at hand, here’s the excerpted passage:

“I made a great study of theology at one time,” said Mr Brooke, as if to explain the insight just manifested. “I know something of all schools. I knew Wilberforce in his best days. Do you know Wilberforce?

“Mr Casaubon said, “No.”

“Well, Wilberforce was perhaps not enough of a thinker; but if I went into Parliament, as I have been asked to do, I should sit on the independent bench, as Wilberforce did, and work at philanthropy.”

Mr Casaubon bowed, and observed that it was a wide field.

“Yes,” said Mr Brooke, with an easy smile, “but I have documents. I began a long while ago to collect documents. They want arranging, but when a question has struck me, I have written to somebody and got an answer. I have documents at my back. But now, how do you arrange your documents?”

“In pigeon-holes partly,” said Mr Casaubon, with rather a startled air of effort.

“Ah, pigeon-holes will not do. I have tried pigeon-holes, but everything getsmixed in pigeon-holes: I never know whether a paper is in A or Z.”

“I wish you would let me sort your papers for you, uncle,” said Dorothea. “I would letter them all, and then make a list of subjects under each letter.

“Mr Casaubon gravely smiled approval, and said to Mr Brooke, “You have an excellent secretary at hand, you perceive.”

“No, no,” said Mr Brooke, shaking his head; “I cannot let young ladies meddle with my documents. Young ladies are too flighty.

“Dorothea felt hurt. Mr Casaubon would think that her uncle had some special reason for delivering this opinion, whereas the remark lay in his mind as lightly as the broken wing of an insect among all the other fragments there, and a chance current had sent it alighting on her.

When the two girls were in the drawing-room alone, Celia said—

“How very ugly Mr Casaubon is!”

“Celia! He is one of the most distinguished-looking men I ever saw. He is remarkably like the portrait of Locke. He has the same deep eye-sockets.”

—George Eliot in Middlemarch (Norton Critical Edition, 2nd edition, Bert G. Hornback ed., 2000), Book I, Chapter 2, p13.

I’d mentioned that my Steelcase card index came without the traditional card stops/follower blocks at the back of the drawers. Needing a solution for this, I’ve discovered that my local Daiso sells small, simple bookends for $1.75 for a pair and they’re the perfect size (7 x 8.9 x 9.2 cm) for the drawers. These seem to do the trick nicely, though they do tend to slide within the metal drawers without any friction. Giving them small rubber feet or museum putty from the hardware store for a few cents more fixes this quickly.

It covers variations of personal knowledge management, commonplace books, zettelkasten, indexing, etc. I wish we’d had time for so much more, but I hope some of the ideas and examples are helpful in giving folks some perspective on what has gone before so that we might expand our own horizons.

The color code of the slides (broadly):

- orange – intellectual history

- dark grey – memory, method of loci, memory palaces

- blue – commonplace books

- green – index cards, slips, zettelkasten traditions

- purple – orality

- light teal – dictionary compilations

- red – productivity methods

Steelcase 8 Drawer Steel Card Index Filing Cabinet for 4 x 6 inch cards

This one is is a 20 gauge solid steel behemoth Steelcase in black and silver powder coat and it is in stunning condition with all the hardware. It stands 52 1/4 inches tall, is 14 7/8 inches wide, and 28 1/2 inches deep (without hardware). Each drawer had two rows of card storage space totaling 55 inches. With 8 drawers, this should easily hold 61,000 index cards.

Sadly, someone has removed all the card following blocks. I’ll keep an eye out for replacements, but I’m unlikely to find some originals, though I could probably also custom design my own. In the meanwhile I find that a nice heavy old fashioned glass or a cellophaned block of 500 index cards serve the same functionality. The drawer dimensions are custom made for 4 x 6 inch index cards, but A6 cards and Exacompta’s 100 x 150mm cards fit comfortably as well.

Based on the styling, I’m guessing it dates from the 1940s to early 1960s, but there are no markings or indications, and it will take some research to see if I can pin down a more accurate date.

A few of the indexing label frames on the unit are upside down and one or two are loose, but that’s easily fixed by removing a screw and cover plate in the front of the drawer and making a quick adjustment. I’ve also got a few extra metal clips to fix the loose frames.

Much like my Singer card index, this one has internal sliding metal chassis into which the individual drawers sit. This allows them to be easily slid out of the cabinet individually for use on my desk or away from the cabinet. The drawers come with built-in handles at the back of the drawer for making carrying them around as trays more comfortable. The drawers are 10.6 pounds each, each chassis is 4.6 pounds, and the cabinet itself is probably 120 pounds giving the entire assembly a curb weight of about 240 pounds. Given that 7,000 index cards weight 29.3 pounds, fully loaded the cabinet and cards would weigh almost 500 pounds.

Placed just behind my desk, I notice that the drawer width is just wide enough, that I can pull out the fourth drawer from the bottom and set my Smith-Corona Clipper on top of it. This makes for a lovely makeshift typing desk. The filing cabinet’s black powder coat is a pretty close match to that of the typewriter.

I’ve already moved the majority of my cards into it and plan to use it as my daily driver. This may mean that the Singer becomes overflow storage once I’m done refurbishing it. The Shaw-Walker box, which was just becoming too full and taking up a lot of desk real estate, will find a life in the kitchen or by the bar as my recipe box.

I’ve also noticed that some of my smaller 3 x 5″ wooden card indexes sit quite comfortably into the empty drawers as a means of clearing off some desk space if I wish. Of course, the benefit of clearing off some desk space for that means that I can now remove individual drawers for working with large sections at a time.

This may be my last box acquisition for a while. Someone said if I were to add any more, I’ll have moved beyond hobbyist collector and into the realm of museum curator.

The best part of the size and shape of the drawers is that until its full of index cards, I can use some of the additional space for a variety of additional stationery storage including fountain pens, ink, stamps, stamp pads, pen rolls, pencils, colored pencils, tape, washi, typewriter ribbon, stencils etc. One of the drawers also already has a collection of 3.5 x 5.5 inch pocket notebooks (most are Field Notes) which are also easily archivable within it.

Book Club on Cataloging the World and Index, A History of the

- Wright, Alex. Cataloging the World: Paul Otlet and the Birth of the Information Age. Oxford University Press, 2014.

- Duncan, Dennis. Index, A History of the: A Bookish Adventure from Medieval Manuscripts to the Digital Age. 1st Edition, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 2022.

This iteration of the book club might be fruitful for those interested in note taking, commonplacing, or zettelkasting. If you’re building or designing a note taking application or attempting to create one for yourself using either paper (notebooks, index cards) or digital tools like Obsidian, Logseq, Notion, Bear, TinderBox etc. having some background on the history and use of these sorts of tools for thought may give you some insight about how to best organize a simple, but sustainable digital practice for yourself.

The first session will be on Saturday, February 17 24, 2024 and recur weekly from 8:00 AM – 10:00 Pacific. Our meetings are usually very welcoming and casual conversations over Zoom with the optional beverage of your choice. Most attendees are inveterate note takers, so there’s sure to be discussion of application of the ideas to current practices.

To join and get access to the Zoom links and the shared Obsidian vault we use for notes and community communication, ping Dan Allosso with your email address.

Happy reading!

Incidentally, if you’re still into the old-school library card catalog cards, Demco still sells the red ruled cards!

Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.’s Zettelkasten

I’ve tracked down where most of his card index is hiding at Morehouse College, but it doesn’t appear to be digitized in any fashion. Interested researchers can delve into the Morehouse College Martin Luther King, Jr. Collection: Series 4: Research Notes, Collection Identifier: 0000-0000-0000-0131i

The following seems to be the bulk of where MLK’s zettelkasten is maintained, in particular:

Who wants to make a road trip to Atlanta to look at some of the most influential index cards of the 20th century?!!

Jillian Hess has recently written a few short notes on MLK’s nachlass and note taking for those interested in some additional insight as well as an example of a quote on one of his 1953 note cards on Amos 5: 21-24 making it into his infamous speech “Normalcy, Never Again” (aka the “I Have a Dream” speech).

I frequently hear students ask if maintaining a zettelkasten for their studies is a worthwhile pursuit. Historically, it was one of the primary uses of the tool, and perhaps this example from one of the 20th century’s greatest orators’ doctoral work at Boston University dating from roughly 1952-1955 will be inspiring.

On Cohesion and Coherence of the Zettelkasten: Where Does the Work Reside?

To assume, that Eminem had a Zettelkasten because he had slips and a box is the same assuming that people are just sacks full of meat. The mere presence of parts is not enough to assume that there is a whole.

You can borrow the terms from linguistics: You need cohesion for the formal wholeness of your Zettelkasten (links, separate notes, etc.) and to have a good Zettelkasten, you need coherence (the actual connections between ideas). Eminem’s box has neither cohesion nor coherence. It is almost the perfect example of what a Zettelkasten is not in the presence of its parts.

The key questions at play here are where is the work of a keeping a zettelkasten done and how is represented? Where is the coherence held? Is the coherence even represented physically? Does it cohere in the box or elsewhere?

The desk in my office (and that of countless others’) can appear to be a hodgepodge of stacks of paper and utter mess. Some might describe it as a disaster area and wonder how I manage to get any work done. However, if asked, I can pull out the exact book, article, paper, or other item required from any of the given piles. This is because internally, I can remember what all the piles represent and, within a reasonable margin of error, what is in each and almost exactly where it is at, or even if it’s filed away in another room. Others, who have no experience with my internal system would be terrifyingly lost in a morass of paper. The system represented by my desk is an extension of my mind, but one which doesn’t need to be directly labeled, classified, or indexed for it to operate properly in my life and various workflows. One could say that the loose categorization of piles is the lowest level of work I could put into the system for it to still be useful for me. However, to those on the outside, this work appears to be wholly missing as they don’t have access to the information and experiences with it that are held only in my brain.

By direct analogy, I suspect that Eminem’s zettelkasten, and that of many others, follows this same pattern. They neither require internal “cohesion nor coherence” in their systems which are direct extensions of their minds where that cohesion and coherence are stored. As far back as Andreas Stübel (1684), many (including Niklas Luhmann) have used variations of the idea “secondary memory” to describe their excerpting and note taking practices. [1][2] Many in the long tradition of ars excerpendi have created piles of slips which held immense value for them. So much so that they would account for them in their wills to give to others following their deaths. In many cases, these piles were wholly useless to their recipients because they were missing all of the context in which they were made and why. Lacking this context, they literally considered them scrap heaps and often unceremoniously disposed of them.

In the case of Niklas Luhmann’s zettelkasten, he spent the additional time and work to index and file his notes thereby making them more comprehensible and possibly of more direct use to people following his death. For his working style and needs, he surely benefited from this additional work, particularly when taken over the longer horizon of his zettelkasten’s “life” compared to others’. However, it’s not always the case that others will have those same needs. Some may only want or need to keep theirs for the length of their undergraduate or graduate school careers. Others may use them for short projects like articles or a single book. This doesn’t mean that there isn’t coherence, it may just be held in their memories for the length of time for which they need it. Those who have problems with longer term memory for things like this may be well-advised to follow Luhmann’s example, particularly when they’re working at problems for career-long spans.

In Eminem’s case, given the shape and size of his collection, which includes various sizes, types, and colors of paper and even different pen colors, it may actually be easier for him to have a closer visual relationship with his notes in terms of finding and using them. (“Yes, that’s the scrap I wrote for 8 Mile while I was at that hotel in Paris. Where is the blue envelope with the doggerel I wrote for my daughter?”) It’s also possible that for his creative needs, sifting through bits and pieces may spark additional creative work in addition to the slips of work he’s already created. Cohesion and coherence may not exist in his notes for us as distant viewers of them, but this doesn’t mean that they do not exist for him while using his box of notes.

As an even more complex example, we might look at the zettelkasten of S.D. Goitein. His has a form closer to that of the better known commonplacing practices of Robert Greene and Ryan Holiday. While Goitein had a collection of only 27,000 notes (roughly a third of Luhmann’s), he had a significantly larger written output of books and articles than Luhmann. Additionally, Goitein’s card index has been scanned and continues to circulate amongst scholars in his areas of expertise by means of physical copies rather than a digitized repository the way that Luhmann’s has over the past decade. Despite Goitein’s notes not having the same level of direct cohesion or coherence as Luhmann’s, I suspect that far more researchers are actively and profitably using Goitein’s collection today than are using Luhmann’s.

For those who are more visually inclined, an additional example of the hidden work of cohesion and coherence can be seen in the example of Victor Margolin.

In this case, Margolin is certainly actively creating both cohesion and coherence. The question is where does it reside? Certainly, like many of us, some of it resides internally in his mind and in coordination with the extension of it represented in his note cards, but as he progresses in his work, much of it goes into his larger outlines drawn out on A2 paper, and ultimately accretes into the writing that appears in the final version of his book World History of Design.

As described in his video, Margolin doesn’t appear to be utilizing his slips as lifelong tools for other potential projects, nor is he heavily indexing or categorizing them the way Luhmann and others have done. This doesn’t make his zettelkasten any less valuable to him, it only changes where the representation of the work is located.

Naturally, for those with lifelong uses of and needs for a zettelkasten, it may make more sense for them to put the work into it in such a way that it appears more cohesive and coherent to external viewers as well as for their future selves, but the variety of methods in the broader tradition, make it fairly simple for individual users to pick and choose where they’d personally like to store representations of their work. If you’re like philosopher Gilles Deleuze[3] who said in L’Abécédaire

And everything that I learn, I learn for a particular task, and once it’s done, I immediately forget it, so that if ten years later, I have to–and this gives me great joy—if I have to get involved with something close to or directly within the same subject, I would have to start again from zero, except in certain very rare cases…

then perhaps you may wish to have better notes with the work cohered directly to, in, and between your cards? Surely Deleuze didn’t start completely from scratch each time because in reality, he had a lifetime’s worth of experience and study to draw from, but he still had to start from what he could remember and begin writing, arguing, and working from there.

This is why having a lifelong zettelkasten practice is more productive for most: it acts as a knowledge ratchet to prevent having to start from scratch by staring at a blank piece of paper. The benefit is that—based on your personal abilities and preferences—you can start somewhere simple and build from there.

Finally, I’ll mention that in Paper Machines, Markus Krajewski calls Joachim Jungius’ the “first practitioner of nonhierarchical indexing”. In talking about the idiosyncratic nature of Jungius’ zettelkasten for which “There are no aids for access, no apparatus; neither signatures nor a numbering of the cards, neither registers nor indexes, let alone referential systems that guide one to the building blocks of knowledge.” he says[4]:

The architecture of the idiosyncratic scholar’s machine requires no mediation for, or access by, others. In dialog with the machine, an intimate communication is permitted. Only the close and confidential dialog results in the connections that lead an author to new texts. When queried by the uninitiated, the box of paper slips remains silent. It is literally a discreet/discrete machine.

If this is the case, then Marshall Mathers is surely channeling Jungius’ practices, as I suspect that many are.

Perhaps in The Merchant of Venice, Shakespeare may have just as profitably written:

Tell me where is knowledge bred?

Or in the box or in the head?

References

My impression is that human brains are very much of a pattern, that under the same conditions they react in the same way, and that were it not for tradition, upbringing, accidents of circumstance, and particularly of accidental individual obsessions, we should find ourselves—since we all face the same universe—much more in agreement than is superficially apparent. We speak different languages and dialects of thought and can even at times catch ourselves flatly contradicting one another in words while we are doing our utmost to express the same idea. How often do we see men misrepresenting one another in order to exaggerate a difference and secure the gratification of an argumentative victory!

—H. G. Wells, “The Idea of a World Encyclopedia.” Harper’s Magazine, April 1937. https://harpers.org/archive/1937/04/the-idea-of-a-world-encyclopedia/.

I’ll agree with Wells that most of our difference here is nitpicking for the sake of argument itself rather than actual meaning.

Because we’re in a holiday season, I’ll use our holiday traditions to analogize why I view things more broadly and prefer the phrase “zettelkasten traditions”. Much of Western society uses the catch-all phrase “Happy Holidays” to subsume a variety of specific holidays encompassing Christmas, Hannukah, New Years, Kwanzaa, and some even the comedically invented holiday of Festivus (“for the rest of us”). Each of these is distinct in its meaning and means of celebration, but each also represents a wide swath of ideas and means of celebration. Taking Christmas as an example: Some celebrate it in a religious framing as the birth of Christ (though, in fact, there is no solid historical attestation for the day of his birth). Some celebrate it as an admixture of Christianity and pagan mid-winter festivities which include trees, holly, mistletoe, lights, a character named Santa Claus, and even elves and reindeer which wholly have nothing to do with Jesus. Some give gifts and some don’t. Some put up displays of animals and mangers while others decorate with items from a 2003 New Line Cinema film starring Will Farrell. Some sing about a reindeer with a red nose created in 1939 as an inexpensive advertising vehicle in a coloring book. Almost everyone differs wildly in both the why and how they choose to celebrate this one particular holiday. The majority choose not to question it, though some absolutists feel that the Jesus-only perspective is what defines Christmas.

I have only touched on the other holidays, each of which has its own distribution of ideas, beliefs, and means of celebration. And all of these we wrap up in an even broader phrase as “Happy Holidays” to inclusively capture them all. Collectively we all recognize what comprises them and defines them, generally focusing on what makes them mean something to us individually. Less frequently do we focus in on what broadly defines them in aggregate because the distribution of definitions is so spectacularly broad. Culturally trying to create one and only one definition is a losing proposition, so why bother beyond attributing the broader societal definitions, which assuredly will change and shift over time. (There was certainly a time during which Christmas was celebrated without any trees or carols, and a time after which there was.)

Zettelkasten traditions have a similar very broad set of definitions and practices, both before Herr Luhmann and after. Assuredly they will continue to evolve. One can insist their own personal definition is the “true one”, while others are sure to insist against it. Spending even a few moments reading almost anything about zettelkasten, one is sure to encounter half a dozen versions. I quite often see people (especially in the Obsidian space) say that they are keeping a zettelkasten, when on a grander scheme of distributions in the knowledge management space, what they’re practicing is far closer to a digital commonplace book than something Luhmann would recognize as something built on his own model, which itself was built on a card index version of a commonplace book, though in his case, one which prescribed a lot of menial duplication by hand. The idiosyncratic nature of the varieties of software and means of making a zettelkasten is perforce going to make a broad definition of what it is. Neither Marshall Mathers nor Chris Rock are prone to call their practices zettelkasten—primarily because they speak English—but they would both very likely recognize the method as a close variation to what they’ve been doing all along.

Humankind has had various instantiations of sense making, knowledge keeping, and transmission over the millennia classified under variations of names from talking rocks, menhir, songlines, Tjukurpa, standing stones, massebah, henges, ars memoria, commonplaces, florilegia, commonplace books, card indexes, wikis, zettelkasten and surely thousands of other names. While they may shift about in their methods of storage, means of operation, and the amount of work both put into them as well as value taken out, they’re part of a broader tradition of human sense making, learning, memory, and creation that brings us to today.

Perhaps it’s worth closing with a sententia from Terence‘s (161 BC), comedy Phormio (line 454)?

Quot homines tot sententiae: suo’ quoique mos.

Translation: “There are as many opinions as there are people who hold them: each has his own correct way.” Given the limitations of the Latin and the related meanings of sententiae, one could almost be forgiven for translating it as “zettelkasten”… Perhaps we should consult the zettelkasten that is represented by the Thesaurus Linguae Latinae?

Why not?

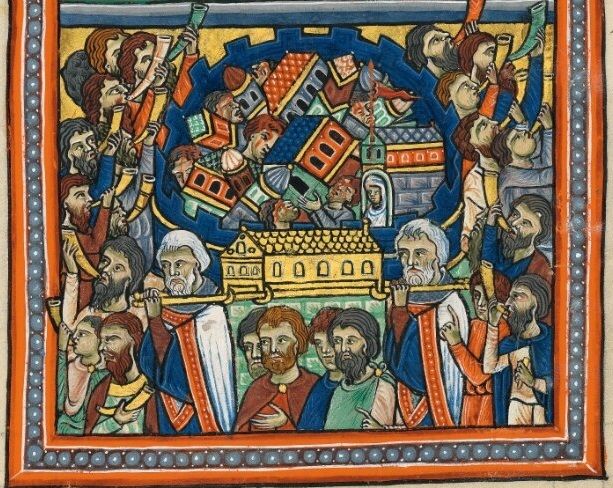

On the seventh day of the siege of Jericho, the Ark of the Covenant is carried around the city, horns are blown and the walls collapse (Josh 6:20-25).

Extract from Latin Psalter from England – BSB Hss Clm 835, fol. 21r. Oxford, 1st quarter of the 13th century

Source: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0