Tag: personal knowledge management

It covers variations of personal knowledge management, commonplace books, zettelkasten, indexing, etc. I wish we’d had time for so much more, but I hope some of the ideas and examples are helpful in giving folks some perspective on what has gone before so that we might expand our own horizons.

The color code of the slides (broadly):

- orange – intellectual history

- dark grey – memory, method of loci, memory palaces

- blue – commonplace books

- green – index cards, slips, zettelkasten traditions

- purple – orality

- light teal – dictionary compilations

- red – productivity methods

Why not?

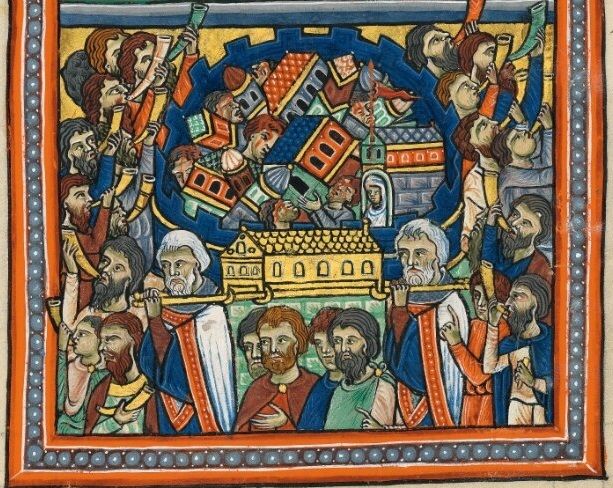

On the seventh day of the siege of Jericho, the Ark of the Covenant is carried around the city, horns are blown and the walls collapse (Josh 6:20-25).

Extract from Latin Psalter from England – BSB Hss Clm 835, fol. 21r. Oxford, 1st quarter of the 13th century

Source: München, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KkQy-Yb0QLE

Knowing What We Know: The Transmission of Knowledge From Ancient Wisdom to Modern Magic by Simon Winchester

Many are certain to know his award winning 1998 book The Professor and the Madman which was also transformed into the eponymous 2019 film starring Sean Penn. Though he didn’t use the German word zettelkasten in the book, he tells the story of philologist James Murray’s late 1800s collaborative 6 million+ slip box collection of words and sentences which when edited into a text is better known today as the Oxford English Dictionary.

If you need some additional motivation to check out his book, I’ll use the fact that Winchester, as a writer, is one of the most talented non-linear storytellers I’ve ever come across, something which many who focus on zettelkasten output may have a keen interest in studying.

Book club anyone? (I’m sort of hoping that Dan Allosso’s group will pick it up as one of their next books after Donut Economics, but I’m game to read it with others before then.)

Book released on 4/25/2023; Book acquired on 4/26/2023

A note about my article on Goitein with respect to Zettelkasten Output Processes

I’m hoping that this example will give the aspiring interested note takers, commonplacers, and zettelkasten maintainers a peek into a small portion of my own specific process if they’d like to look more closely at such an example.

Following the reading and note taking portions of the process, I spent about 5 minutes scratching out a brief outline for the shape of the piece onto one of my own 4 x 6″ index cards. I then spent 15 minutes cutting and pasting all of what I felt the relevant notes were into the outline and arranging them. I then spent about two hours writing and (mostly) editing the whole. In a few cases I also cut and pasted a few things from my digital notes which I also felt would be interesting or relevant (primarily the parts on “notes per day” which I had from prior research.) All of this was followed by about an hour on administrivia like references and HTML formatting to put it up on my website. While some portions were pre-linked in a Luhmann-ese zettelkasten sense, other portions like the section on notes per day were a search for that tag in my digital repository in Hypothes.is which allowed me to pick and choose the segments I wanted to cut and paste for this particular piece.

From the outline to the finished piece I spent about three and a half hours to put together the 3,500 word piece. The research, reading, and note taking portion took less than a day’s worth of entertaining diversion to do including several fun, but ultimately blind alleys which didn’t ultimately make the final cut.

For the college paper writers, this entire process took less than three days off and on to produce what would be the rough equivalent of a double spaced 15 page paper with footnotes and references. Naturally some of my material came from older prior notes, and I would never suggest one try to cram write a paper this way. However, making notes on a variety of related readings over the span of a quarter or semester in this way could certainly allow one to relatively quickly generate some reasonably interesting material in a way that’s both interesting to and potentially even fun for the student and which could potentially push the edges of a discipline—I was certainly never bored during the process other than some of the droller portions of cutting/pasting.

While the majority of the article is broadly straightforward stringing together of facts, one of the interesting insights for me was connecting a broader range of idiosyncratic note taking and writing practices together across time and space to the idea of statistical mechanics. This is slowly adding to a broader thesis I’m developing about the evolving life of these knowledge practices over time. I can’t wait to see what develops from this next.

In the meanwhile, I’m happy to have some additional documentation for another prominent zettelkasten example which resulted in a body of academic writing which exceeds the output of Niklas Luhmann’s own corpus of work. The other outliers in the example include a significant contribution to a posthumously published book as well as digitized collection which is still actively used by scholars for its content rather than for its shape. I’ll also note that along the way I found at least one and possibly two other significant zettelkasten examples to take a look at in the near future. The assured one has over 15,000 slips, apparently with a hierarchical structure and a focus on linguistics which has some of the vibes of John Murray’s “slip boxes” used in the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary.

Earnest but still solidifying #pkm take:

The ever-rising popularity of personal knowledge management tools indexes the need for liberal arts approaches. Particularly, but not exclusively, in STEM education.

When people widely reinvent the concept/practice of commonplace books without building on centuries of prior knowledge (currently institutionalized in fields like library & information studies, English, rhetoric & composition, or media & communication studies), that's not "innovation."

Instead, we're seeing some unfortunate combination of lost knowledge, missed opportunities, and capitalism selectively forgetting in order to manufacture a market.

Are you collecting examples of things for students? (seeing examples can be incredibly powerful, especially for defining spaces) for yourself? Are you using them for exploring a particular space? To clarify your thinking/thought process? To think more critically? To write an article, blog, or book? To make videos or other content?

Your own website is a version of many of these things in itself. You read, you collect, you write, you interlink ideas and expand on them. You’re doing it much more naturally than you think.

—

I find that having an idea of the broader space, what various practices look like, and use cases for them provides me a lot more flexibility for what may work or not work for my particular use case. I can then pick and choose for what suits me best, knowing that I don’t have to spend as much time and effort experimenting to invent a system from scratch but can evolve something pre-existing to suit my current needs best.

It’s like learning to cook. There are thousands of methods (not even counting cuisine specific portions) for cooking a variety of meals. Knowing what these are and their outcomes can be incredibly helpful for creatively coming up with new meals. By analogy students are often only learning to heat water to boil an egg, but with some additional techniques they can bake complicated French pâtissier. Often if you know a handful of cooking methods you can go much further and farther using combinations of techniques and ingredients.

What I’m looking for in the reading, note taking, and creation space is a baseline version of Peter Hertzmann’s 50 Ways to Cook a Carrot combined with Michael Ruhlman’s Ratio: The Simple Codes Behind the Craft of Everyday Cooking. Generally cooking is seen as an overly complex and difficult topic, something that is emphasized on most aspirational cooking shows. But cooking schools break the material down into small pieces which makes the processes much easier and more broadly applicable. Once you’ve got these building blocks mastered, you can be much more creative with what you can create.

How can we combine these small building blocks of reading and note taking practices for students in the 4th – 8th grades so that they can begin to leverage them in high school and certainly by college? Is there a way to frame them within teaching rhetoric and critical thinking to improve not only learning outcomes, but to improve lifelong learning and thinking?

@flancian @JerryMichalski @MathewLowry @Borthwick @dwhly @An_Agora @ZsViczian

https://cosma.graphlab.fr/en/docs/user-manual/

This week John Borthwick put out a call for Tools for Thinking: People want better tools for thinking — ones that take the mass of notes that you have and organize them, that help extend your second brain into a knowledge or interest graph and that enable open sharing and ownership of the “knowl...

I’ll always maintain that Vannevar Bush really harmed the first few generations of web development by not mentioning the word commonplace book in his conceptualization. Marks heals some of this wound by explicitly tying the idea of memex to that of the zettelkasten however. John Borthwick even mentions the idea of “networked commonplace books”. [I suspect a little birdie may have nudged this perspective as catnip to grab my attention—a ruse which is highly effective.]

Some of Kevin’s conceptualization reminds me a bit of Jerry Michalski’s use of The Brain which provides a specific visual branching of ideas based on the links and their positions on the page: the main idea in the center, parent ideas above it, sibling ideas to the right/left and child ideas below it. I don’t think it’s got the idea of incoming or outgoing links, but having a visual location on the page for incoming links (my own site has incoming ones at the bottom as comments or responses) can be valuable.

I’m also reminded a bit of Kartik Prabhu’s experiments with marginalia and webmention on his website which plays around with these ideas as well as their visual placement on the page in different methods.

MIT MediaLab’s Fold site (details) was also an interesting sort of UI experiment in this space.

It also seems a bit reminiscent of Kevin Mark’s experiments with hovercards in the past as well, which might be an interesting way to do the outgoing links part.

Next up, I’d love to see larger branching visualizations of these sorts of things across multiple sites… Who will show us those “associative trails”?

Another potential framing for what we’re all really doing is building digital versions of Indigenous Australian’s songlines across the web. Perhaps this may help realize Margo Neale and Lynne Kelly’s dream for a “third archive”?

A smidgen of its use stems from the mistranslation of some Luhmann work which is better read as “secondary memory”.

One of my favorites is Eminem’s “stacking ammo“.