Mae’r Gymraeg yn fy ngwneud i’n hapus.

You’d probably also really enjoy Japanese onomatopoeia.

Mae’r Gymraeg yn fy ngwneud i’n hapus.

You’d probably also really enjoy Japanese onomatopoeia.

Six years ago we put our daughter into a dual immersion Japanese program (in the United States) and it has changed some of my view of how we teach and learn languages, a process which is also affected by my slowly picking up conversational Welsh using the method at https://www.saysomethingin.com/ over the past year and change, a hobby which I wish I had more targeted time for.

Children learn language through a process of contextual use and osmosis which is much more difficult for adults. I’ve found that the slowly guided method used by SSiW is fairly close to this method, but is much more targeted. They’ll say a few words in the target language and give their English equivalents, then they’ll provide phrases and eventually sentences in English and give you a few seconds to form them into the target language with the expectation that you try to say at least something, or pause the program to do your best. It’s okay if you mess up even repeatedly, they’ll say the correct phrase/sentence two times after which you’ll repeat it again thus giving you three tries at it. They’ll also repeat bits from one lesson to the next, so you’ll eventually get it, the key is not to worry too much about perfection.

Things slowly build using this method, but in even about 10 thirty minute lessons, you’ll have a pretty strong grasp of fluent conversational Welsh equivalent to a year or two of college level coursework. Your work on this is best supplemented with interacting with native speakers and/or watching television or reading in the target language as much as you’re able to.

For those who haven’t experienced it before I’d recommend trying out the method at https://www.saysomethingin.com/welsh/course1/intro to hear it firsthand.

The experience will give your brain a heavy work out and you’ll feel mentally tired after thirty minutes of work, but it does seem to be incredibly effective. A side benefit is that over time you’ll also build up a “gut feeling” about what to say and how without realizing it. This is something that’s incredibly hard to get in most university-based or book-based language courses.

This method will give you quicker grammar acquisition and you’ll speak more like a native, but your vocabulary acquisition will tend to be slower and you don’t get any writing or spelling practice. This can be offset with targeted memory techniques and spaced repetition/flashcards or apps like Duolingo that may help supplement one’s work.

I like some of the suggestions made in Lynne Kelly’s post about Chinese as I’ve been pecking away at bits of Japanese over time myself. There’s definitely an interesting structure to what’s going on, especially with respect to the kana and there are many similarities to what is happening in Japanese to the Chinese that she’s studying. I’m also approaching it from a more traditional university/book-based perspective, but if folks have seen or heard of a SSiW repetition method, I’d love to hear about it.

Hopefully helpful by comparison, I’ll mention a few resources I’ve found for Japanese that I’ve researched on setting out a similar path that Lynne seems to be moving.

Japanese has two different, but related alphabets and using an app like Duolingo with regular practice over less than a week will give one enough experience that trying to use traditional memory techniques may end up wasting more time than saving, especially if one expects to be practicing regularly in both the near and the long term. If you’re learning without the expectation of actively speaking, writing, or practicing the language from time to time, then wholesale mnemotechniques may be the easier path, but who really wants to learn a language like this?

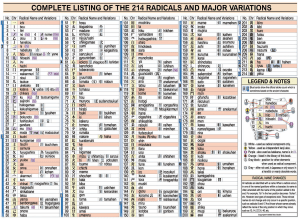

The tougher portion of Japanese may come in memorizing the thousands of kanji which can have subtly different meanings. It helps to know that there are a limited set of specific radicals with a reasonably delineable structure of increasing complexity of strokes and stroke order.

The best visualization I’ve found for this fact is the Complete Listing of the 214 Radicals and Major Variations from An Introduction to Japanese Kanji Calligraphy by Kunii Takezaki (Tuttle, 2005) which I copy below:

(Feel free to right click and view the image in another tab or download it and view it full size to see more detail.)

I’ve not seen such a chart in any of the dozens of other books I’ve come across. The numbered structure of increasing complexity of strokes here would certainly suggest an easier to build memory palace or songline.

I love this particular text as it provides an excellent overview of what is structurally happening in Japanese with lots of tidbits that are otherwise much harder won in reading other books.

There are many kanji books with various forms of what I would call very low level mnemonic aids. I’ve not found one written or structured by what I would consider a professional mnemonist. One of the best structured ones I’ve seen is A Guide to Remembering Japanese Characters by Kenneth G. Henshall (Tuttle, 1988). It’s got some great introductory material and then a numbered list of kanji which would suggest the creation of a quite long memory palace/journey/songline.

Each numbered Kanji has most of the relevant data and readings, but provides some description about how the kanji relates or links to other words of similar shapes/meanings and provides a mnemonic hint to make placing it in one’s palace a bit easier. Below is an example of the sixth which will give an idea as to the overall structure.

I haven’t gotten very far into it yet, but I’d found an online app called WaniKani for Japanese that has some mnemonic suggestions and built-in spaced repetition that looks incredibly promising for taking small radicals and building them up into more easily remembered complex kanji.

I suspect that there are likely similar sources for these couple of books and apps for Chinese that may help provide a logical overall structuring which will make it easier to apply or adapt one’s favorite mnemotechniques to make the bulk vocabulary memorization easier.

The last thing I’ll mention I’ve found, that’s good for practicing writing by hand as well as spaced repetition is a Kanji notebook frequently used by native Japanese speaking children as they’re learning the levels of kanji in each grade. It’s non-obvious to the English speaker, and took me a bit to puzzle out and track down a commercially printed one, even with a child in a classroom that was using a handmade version. The notebook (left to right and top to bottom) has sections for writing a big example of the learned kanji; spaces for the “Kun” and “On” readings; spaces for the number of strokes and the radical pieces; a section for writing out the stroke order as it builds up gradually; practice boxes for repeated practice of writing the whole kanji; examples of how to use the kanji in context; and finally space for the student to compose their own practice sentences using the new kanji.

Regular use and practice with these can be quite helpful for moving toward mastery.

I also can’t emphasize enough that regularly and actively watching, listening, reading, and speaking in the target language with materials that one finds interesting is incredibly valuable. As an example, one of the first things I did for Welsh was to find a streaming television and radio that I want to to watch/listen to on a regular basis has been helpful. Regular motivation and encouragement is key.

I won’t go into them in depth and will leave them to speak for themselves, but two of the more intriguing videos I’ve watched on language acquisition which resonate with some of my experiences are:

Starting an experiment of the month, and succumbing to my curiosity around Python.

I’m also glad to have stumbled across this so serendipitously for its mention of WaniKani for learning 日本語 (Japanese) kanji. I’m not quite sure what to make of their Crabigator yet, but perhaps Jack Jamieson might appreciate this as well.

I’ve been trying to catch up to a fourth grader in a dual immersion program, and I’ve been falling behind lately while working on my Welsh project. I’ve been too (slowly) working on a memory palace of Kanji with a lot more detail and historical information based on Kenneth Henshall’s A Guide To Remembering Japanese Characters, which seems to be one of the best texts I’ve seen for raw data. This app looks like it uses mnemonic associations in a different way along with spaced repetition that might allow for better immediate fluency.

Naturally I’m always happy to come across apps purporting to use mnemonics and spaced repetition, though I am still search for something with a more fluent focus for Japanese that is similar to SSiW’s immersion method.

I’m pained to discover that @HBOMax only has English dubs of the Studio Ghibli collection. I was really hoping for the originals in Japanese.

So for “pretty” as kekkou, type ke-k-ko-u which transforms to けっこうautomatically.

Handwritten kanji recognition. Draw a kanji in the box with the mouse. The computer will try to recognize it. Be careful about drawing strokes in the correct order and direction.

Free stories for kids of all ages. Audible Stories is a free website where kids of all ages can listen to hundreds of Audible audio titles across six different languages—English, Spanish, French, German, Italian and Japanese—for free, so they can keep learning, dreaming and just being kids.

Japanese difficult? Study boring? No way! Not with this “real manga, real Japanese” approach to learning. Presenting all spoken Japanese as a variation of three basic sentence types, Japanese the Manga Way shows how to build complex constructions step by step. Every grammar point is illustrated by an actual manga published in Japan to show how the language is used in real life, an approach that is entertaining and memorable. As an introduction, as a jump-start for struggling students, or (with its index) as a reference and review for veterans, Japanese the Manga Way is perfect for all learners at all levels.

- The felt mat size: 31.5 x 51.18 x 0.12 inch (80 x 130 cm x 3 mm).

- Good quality. Thickened felt pad, it contains wool material.

- Can be hold your paper and keep the table clean, you won't get ink on your desk.

- Can be used for practice calligraphy/sumi and drawing, perfect for beginners and Chinese lovers.

- Easy to carry and easy to use.

A Japanese Dictionary

It’s been far too long since I’ve had this opened and practiced. I really need to get back to it on a regular basis.

Reviewed over pre-lesson D and Lesson 1

March 1, 2019-March 3, 2019 at Billy Wilder Theater

During the silent film era in Japan, which extended into the early 1930s, film screenings were accompanied by live narrators, called benshi. In the industry’s early years, benshi functioned much in the way scientific lecturers did in early American and European cinema, providing simple explanations about the new medium and the moving images on screen. Soon, however, benshi developed into full-fledged performers in their own right, enlivening the cinema experience with expressive word, gesture and music. Each with their own highly refined personal style, they deftly narrated action and dialogue to illuminate—and often to invent—emotions and themes that heightened the audience’s connection to the screen. Loosely related to the style of kabuki theater in which vocal intonation and rhythm carries significant meaning and feeling, benshi evolved in its golden age, between 1926-1931, as an art form unto itself. Well-established benshi such as Tokugawa Musei, Ikukoma Raiyfi, and Nakamura Koenami were treated as stars, reviewed by critics, featured in profiles (in 1909, the first issue of one of Japan’s earliest film journals featured a benshi on its cover) and commanded high salaries from exhibitors. The prominence and significant cultural influence of benshi prompted the government to try to regulate their practice, instituting a licensing system in 1917 and attempts were made to enhance their role as “educators” through training programs overseen by the Ministry of Education. The benshi were not without controversy, however. While some contemporary critics argued that the benshi were essential to differentiating Japanese film culture from the rest of the world’s output, others argued that the benshi, along with other theatrical elements, impeded the artistic and technical evolution of Japanese cinema into a fully modern art form. Benshi did vigorously resist the coming of sound to Japanese cinema and the practice continued, though with increasing rarity, into the sound era. The art, today, is carried on by a small group of specialized performers who have been apprenticed by the preceding generations of benshi, creating a continuous lineage back to the original performers.

The Archive and the Tadashi Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japanese Humanities are pleased to present this major benshi event in Los Angeles which will afford audiences a once-in-a-lifetime chance to experience this unique art form in all its rich textures. Pairing rare prints of Japanese classics and new restorations of American masterworks, this weekend-long series features performances by three of Japan’s most renowned contemporary benshi, Kataoka Ichirō, Sakamoto Raikō, and Ōmori Kumiko. Trained by benshi masters of the previous generation, they will each perform their unique art live on stage in Japanese (with English subtitles) to multiple films over the course of the weekend. Every performance and screening will be accompanied by a musical ensemble with traditional Japanese instrumentation, featuring Yuasa Jōichi (conductor, shamisen), Tanbara Kaname (piano), Furuhashi Yuki (violin), Suzuki Makiko (flute), Katada Kisayo (drums).

Special thanks to the Tadashi Yanai Initiative for Globalizing Japanese Humanities, The Tsubouchi Memorial Theatre Museum at Waseda University and the Top Global University Project, Global Japanese Studies Model Unit, Waseda University (MEXT Grant), National Film Archive of Japan.

Award-winning author Naomi Hirahara shares the story of the resilience of Japanese Americans transitioning back to freedom and rebuilding their lives after internment as part of the La Pintoresca Associates 3rd annual fundraiser on Sunday, Oct. 21 from 2 to 4 p.m. at Pasadena Public Library’s La Pintoresca Branch, 1355 N. Raymond Ave. Music from EPC Jazz Group, a performance by the Kodama Taiko drummers and a taste of Japanese, Italian and American foods will also be featured. The event is free.