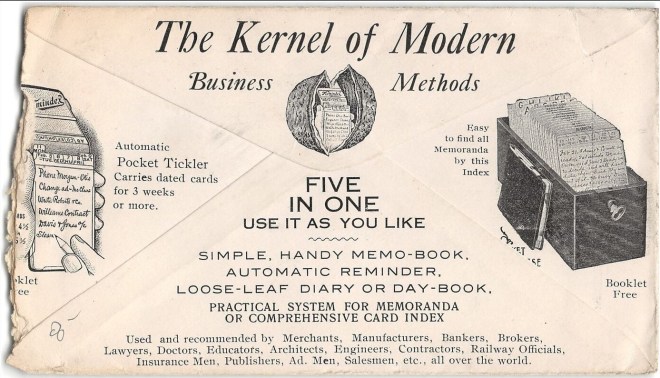

Wilson Memindex Co., Rochester, NY

It was fascinating to run across the Memindex, a productivity tool from the Wilson Memindex Co., advertised in a December 1906 issue of System: The Magazine of Business. Memindex seems to be an obvious portmanteau of the words memory and index.

Let YOUR MIND GO FREE

Do not tax your brain trying to remember. Get the MEMINDEX HABIT and you can FORGET WITH IMPUNITY. An ideal reminder and handy system for keeping all memoranda where they will appear at the right time. Saves time, money, opportunity. A brain saver. No other device answers its purpose. A Great Help for Busy Men, Used and recommended by Bankers, Manufacturers, Salesmen, Lawyers, Doctors, Merchants, Insurance Men, Architects, Educators, Contractors, Railway Managers Engineers, Ministers, etc., all over the world. Order now and get ready to Begin the New Year Right. Rest of ’06 free with each outfit. Express prepaid on receipt of price. Personal checks accepted.

Also a valuable card index for desk use. Dated cards from tray are carried in the handy pocket case, 2 to 4 weeks at a time. To-day’s card always at the front. No leaves to turn. Helps you to PLAN YOUR WORK WORK YOUR PLAN ACCOMPLISH MORE You need it. Three years’ sales show that most all business and professional men need it. GET IT NOW. WILSON MEMINDEX CO. 93 Mills St., Rochester, N. Y.

Early Computer Science Influence?

The Memindex product appears several decades prior to Vannevar Bush’s “coinage” of memex in As We May Think (The Atlantic, July 1945). While many credit Bush for an early instantiation of the internet using the model of a desk, microfiche, and a filing system, almost all of these moving parts had already existed in late 19th century networked office furniture and were just waiting for automation and computerization. The primary difference in this Memindex card system and Bush’s Memex is the higher information density made available through the use of microfiche. Now it turns out his coinage of memex appears to have been in the zeitgeist decades prior as well. I’ve got evidence that the Wilson Memindex was sold well into the early 1950s. (My current dating is to 1952, though later examples may exist.) Below I’ve pictured some cards from the same year as Bush’s now famous piece in the Atlantic.

Most people are more familiar with the popular 20th century magazine System than they realize. Created and published by A. W Shaw, one of the partners of Shaw-Walker, a major manufacturer of office furniture in the early 20th century, the popular magazine was sold to McGraw-Hill Company in 1927/8 and renamed Businessweek which was later sold again and renamed Bloomberg Businessweek.

Relationship to other modern productivity methods

Some will certainly see close ties of this early product to the idea of the “hipster PDA” or Hawk Sugano’s Pile of Index Cards which appeared in 2006. It also doesn’t take much imagination for one to look at the back of a Wilson Memindex envelope from 1909 or an ad from the 1930s to see the similarity to the 43 folders system, bits of Getting Things Done (GTD), or the Bullet Journal methods in common use today. The 1909 envelope also appears to combine a predecessor to the 43 folders idea mixed with the hipster PDA in a coherent pocket and desk-based system.

With alphabetic tabs for the desktop version, one could easily have used this for “Building a Second Brain” as described by modern productivity gurus who almost exclusively suggest digital tools for maintaining their systems now. The 1909 envelop specifically recommends using the system as “comprehensive card index” which is essentially what most second brain or zettelkasten systems are, though there is a broad disconnect between some of this and the reimagining of the zettelkasten in current craze for using Niklas Luhmann-esque organization methods which have some different aims.

What’s interesting beyond the similarities of the systems is the means by which they were sold and spread. Older systems like the Memindex or related general office filing and indexing systems (Shaw-Walker), were primarily selling physical products/hardware like boxes, filing cabinets, holders, cards, and dividers as much as they were selling a process or idea. Mid- and late-century companies like Day-Timer or FranklinCovey also sold physical stationery products (calendars, planners, boxes, binders, books, ) but also began more heavily selling ideas like “productivity” and “leadership”. Modern productivity gurus are generally selling the ideas of the systems and making their money not on the physical items, software or programs which implement them, but with consulting fees, class fees, subscriptions, books which describe their systems, or even advertising against page or video views.

The 1906 version of the Memindex was popular enough to already be offered with the following options of materials for the distinguishing tastes of consumers:

- Cowhide Seal Leather Case and hardwood tray

- Am. Russia Leather Case and plain oak tray

- Genuine Morocco Case and quartered oak tray

What options is your current productivity guru or system offering? What are the differentiations and affordances it’s offering compared to similar systems in the early 1900s? Where is the “rich Corinthian leather“?

The Memindex Method

The basic Memindex method consists of using 2 3/4″ x 4 1/2″ (vest pocket sized) or 3 x 5 1/2″ cards depending on one’s size preference to jot down to do lists or tickler items on individually dated cards which are kept in a desk-based wooden card index with tabs for both months as well as alphabetic tabs in some systems. One then keeps a small pocket-sized card holder with the coming three weeks’ worth of cards on their person for active daily use and files them away as the days go by.

Apparently the truism “everything old is new again” is true yet again.