Tag: brid.gy

Using Facepiles in Comments for WordPress with Webmentions and Semantic Linkbacks

What does this mean? My personal website both sends and accepts Webmentions, a platform independent “at mention” or @mention, including those from the fantastic, free service brid.gy which sends replies/comments, likes, reposts, and mentions to my site from silo services like Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, and even Flickr.

As I’ve long known, and as someone noted at least once on my site, some of these likes, replies, and mentions, which provide some interesting social interaction and social proof of a post’s interest, don’t always contribute to the actual value of the conversation. Now with this wonderful facepiling UI-feature, I’m able to concatenate these types of interactions into a smaller and more concentrated section at the bottom of a post’s comments section, so they’re still logged and available, but now they just aren’t as distracting to the rest of the conversation.

Compare the before and after:

Before

After

A Prime Example

In particular, this functionality can best bee seen on my article The Facebook Algorithm Mom Problem, which has over 400 such interactions which spanned pages and pages worth of likes, reposts, and mentions. Many of my posts only get a handful of these types of interactions, but this particular post back in July was overwhelmed with them when it floated to the top of Hacker News and nearly crippled my website. Without the facepile functionality, the comments section of this post was untenably unreadable and unusable. Now, with facepiles enabled, the comments are more quickly read and more useful to those who are interested in reading them while still keeping the intent.

Implementing

For those who have already begun Indiewebifying their WordPress sites with plugins like Webmention and Semantic Linkbacks, the most recent 3.5.0 update to Semantic Linkbacks has the functionality enabled by default. (Otherwise you can go to your administrative dashboard and click on the checkbox next to “Automatically embed facepile” located under Settings » Discussion).

As a caveat, there’s a known bug for those who are using JetPack to “Let readers use WordPress.com, Twitter, Facebook, or Google+ accounts to comment”. If the facepiles don’t show up on your site, just go to your JetPack settings (at yoursite.com/wp-admin/admin.php?page=jetpack#/discussion) and disable this feature. Hopefully, the JetPack team will have it fixed shortly.

If you haven’t begun using IndieWeb principles on your WordPress website, you might consider starting with my article An Introduction to the IndieWeb, which includes some motivation as well as some great resources for getting started.

Nota bene: I know many in the WordPress community are using the excellent theme Independent Publisher, which already separates out likes, mentions, etc. (though without the actual “facepiles”), so I’m not sure if/how this functionality may work in conjunction with it. If you know, please drop me a note.

Hopefully most WordPress themes will support it natively without any modifications, but users are encouraged to file issues on the plugin if they run across problems.

Using another platform?

I’m not immediately aware of many other CMSes or services that have this enabled easily out of the box, but I do know that Drew McLellan enabled it (along with Webmentions) in the Perch CMS back in July. Others who I’ve seen enabling this type of functionality are documented on the IndieWeb wiki in addition to Marty McGuire and Jeremy Keith, who has a modified version, somewhat like Independent Publisher’s, on his website.

There are certainly many in the IndieWeb community who can help you with this idea (and many others) in the IndieWeb’s online chat.

Give it a spin

Now that it’s enabled, if you’re reading it on my website, you can click on any of the syndicated copies listed below and like, retweet/repost, or mention this article in those social media platforms and your mention will get sent back to my post to be displayed almost as it would be on many of those platforms. Naturally comments or questions are encouraged to further the ongoing conversation, which should now also be much easier to read and interact with.

Thanks again to everyone in the IndieWeb community who are continually hacking away to allow more people to more easily own and control their content while still easily interacting with people on the internet.

UPDATE

Turning mentions into comments for native display

Following Aaron Davis’ comment, I thought I’d add a few more thoughts for those who have begun facepiling their likes, mentions, bookmarks, etc. As he indicates, it’s sometimes useful to call out a particular mention, a special like, or you might want to highlight one among the thousands for a particular reason. This is a feature that many are likely to want occasionally and code for it may be added in the future, but until then, one is left in the lurch a bit. Fortunately, as with all things IndieWeb, part of the point is having more control over your site to be able to do anything you’d like to it. So for those without the ability to write the requisite code to create a pull request against the Webmention or Semantic Linkbacks plugins (they’re more than welcome), here are a few quick cheats for converting that occasional (facepiled or not) webmention into a full comment within your WordPress site’s comment section.

Pro tip: This also works (even if you’re not using facepiles) to convert a basic mention into something that looks more like a native comment. It’s also useful when you’ve received a mention that you’d prefer to treat as a reply, but which wasn’t marked up as a reply by the sending site.

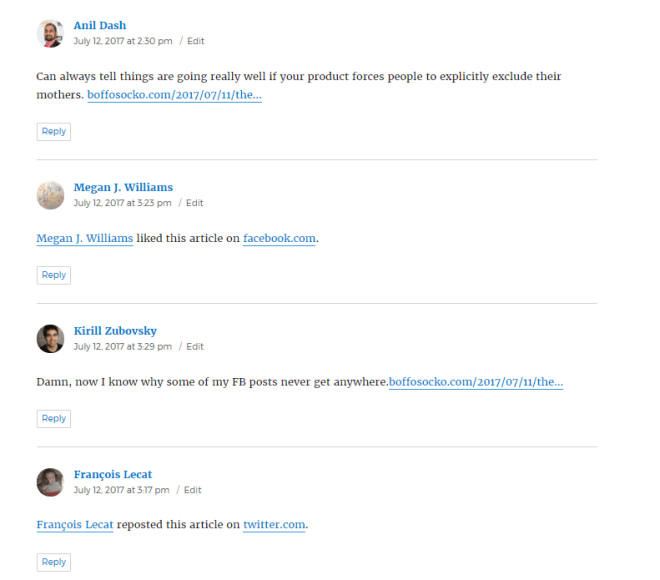

I’ll use an example from the Facebook Algorithm Mom Problem post referenced above. On that post, I’d received a webmention via Twitter from Anil Dash, a blogger and advocate for more humane, inclusive and ethical technology, with some commentary about usability. Here is his original tweet:

Can always tell things are going really well if your product forces people to explicitly exclude their mothers. https://t.co/lh41jVIU0E

— Anil Dash (@anildash) July 12, 2017

That webmention is now hidden behind an avatar and not as likely to be seen by more casual readers. I’d like to change it from being hidden behind his avatar in that long mention list and highlight it a bit to make it appear as a comment in the full comments section.

Steps to convert a mention to a comment

Caution: I recommend reading through all the steps before attempting this. You’ll be modifying your WordPress database manually, so please be careful so you don’t accidentally destroy your site. When doing things like this, it’s always a good idea to make a back up of your database just in case.

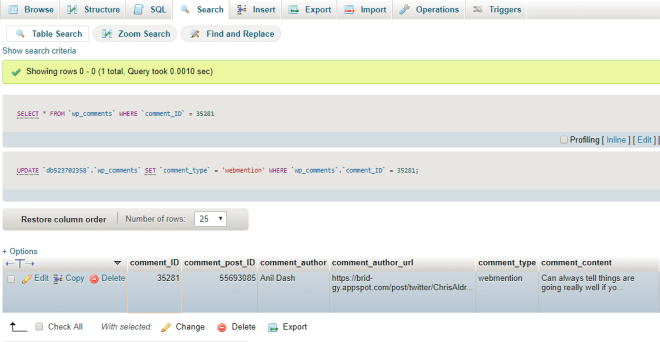

- Search for the particular comment you want to change in the WordPress Admin UI.

- Hover over the date in the “Submitted On” column to find the comment ID number in the URL, in this case it’s

http://boffosocko.com/2017/07/11/the-facebook-algorithm-mom-problem/#comment-35281. Make a note of the comment ID: 35281. - Open up the mySQL database for your WordPress install (I’m using phpMyAdmin) to view the data for your site.

- Go to the

wp_commentstable in the database. (Yours may be slightly different depending on how your site was set up, but it should contain the word “comments”.) - Use the search functionality for your table and input your comment ID number into the field for

comment_ID. - Now delete the word “webmention” from the

comment_typefield for the particular comment. This field should now be empty. - You should now be able to view your post (be sure to clear your cache if necessary) and see the mention you received displayed as a native comment instead of a mention. It should automatically include the text of the particular mention you needed.

If you need to convert a large number of mentions into comments, you may be better off searching for the particular post’s post_ID in the comments table and changing multiple comment_type fields at once. Be careful doing this in bulk–you may wish to do a database back up before making any changes to be on the safe side.

Reply to What the New Webmention and Annotation W3C Standards Mean for WordPress | WPMUDEV

After having used Webmentions on my site for 2+ years, I think you (and the Trackbacks vs Pingbacks vs Webmentions for WordPress article) are heavily underselling their true value. Yes, in some sense they’re vaguely similar to pingbacks and trackbacks, but Webmentions have evolved them almost to the point that they’re now a different and far more useful beast.

I prefer to think of Webmentions as universal @mentions in a similar way to how Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Instagram, Medium and others have implemented their @mentions. The difference is that they work across website boundaries and prevent siloed conversations. Someone could use, for example, their Drupal site (with Webmentions enabled) and write (and also thereby own) their own comment while still allowing their comment to appear on the target/receiving website.

The nice part is that Webmentions go far beyond simple replies/comments. Webmentions can be used along with simple Microformats2 mark up to send other interactions from one site to another across the web. I can post likes, bookmarks, reads, watches, and even listens to my site and send those intents to the sites that I’m using them for. To a great extent, this allows you to use your own website just as you would any other social media silo (like Facebook or Twitter); the difference is that you’re no longer restrained to work within just one platform!

Another powerful piece that you’re missing is pulling in comments and interactions from some of the social services using Brid.gy. Brid.gy bootstraps the APIs of Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, Google+, and Flicker so that they send webmentions. Thus, I can syndicate a post from my WordPress site to Twitter or Facebook and people commenting in those places will be automatically sending their commentary to my original post. This way I don’t really need to use Facebook natively to interact anymore. The added bonus is that if these social sites get shut down or disappear, I’ve got a copy of the full conversation from other places across the web archived in one central location on my personal site!

To add some additional perspective to the value of Webmentions and what they can enable, imagine for a moment if both Facebook and Twitter supported Webmentions. If this were the case, then one could use their Facebook account to comment on a Tweet and similarly one could use their Twitter account to like a Facebook post or even retweet it! Webmentions literally break down the walls that are separating sites on the web.

For the full value of the W3C Webmention spec within WordPress, in addition to the Webmention plugin, I’d also highly recommend Semantic Linkbacks (to make comments and mentions look better on your WordPress site), Syndication Links, and configure Brid.gy. A lot of the basics are documented on the Indieweb wiki.

If it helps to make the entire story clearer and you’d like to try it out, here’s the link to my original reply to the article on my own site. I’ve syndicated that reply to Twitter and Facebook. Go to one of the syndicated copies and reply to it there within either Twitter/Facebook. Webmentions enable your replies to my Twitter/Facebook copies to come back to my original post as comments! And best of all these comments should look as if they were made directly on my site via the traditional comment box. Incidentally, they’ll also look like they should and absolutely nothing like the atrociousness of the old dinosaurs trackbacks and pingbacks.

@Mentions from Twitter to My Website

You can tweet to my website.

One of my favorite things about the indieweb is how much less time I spend on silo sites like Facebook and Twitter. In particular, one of my favorite things is not only having the ability to receive comments from many of these sites back on the original post on my own site, but to have the ability for people to @mention me from Twitter to my own site.

Yes, you heard that right: if you @mention me in a tweet, I’ll receive it on my own website. And my site will also send me the notification, so I can turn off all the silly and distracting notifications Twitter had been sending me.

Below, I’ll detail how I set it up using WordPress, though the details below can certainly be done using other CMSes and platforms.

rel=“me”

On my homepage, using a text widget, I’ve got an h-card with my photo, some basic information about me, and links to various other sites that relate to me and what I’m doing online.

One of these is a link to my Twitter account (see screenshot). On that link I’m using the XFN’s rel=“me” on the link to indicate that this particular link is a profile equivalence of my identity on the web. It essentially says, “this Twitter account is mine and also represents me on the web.”

Here’s a simplified version of what my code looks like:

<a href="https://twitter.com/chrisaldrich" rel=“me">@chrisaldrich</a>

If you prefer to have an invisible link on your site that does the same thing you could alternately use:

<link href="https://twitter.com/twitterhandle" rel=“me">

Similarly Twitter also supports rel=“me”, so all I need to do there is to edit my profile and enter my website www.boffosocko.com into the “website” field and save it. Now my Twitter profile page indicates, this website belongs to this Twitter account. If you look at the source of the page when it’s done, you’ll see the following:

<a class="u-textUserColor" title="http://www.boffosocko.com" href="https://t.co/AbnYvNUOcy" target="_blank" rel="me nofollow noopener">boffosocko.com</a>

Though it’s a bit more complicated than what’s on my site, it’s the rel=“me” that’s the important part for our purposes.

Now there are links on both sites that indicate reciprocally that each is related to the other as versions of me on the internet. The only way they could point at each other this way is because I have some degree of ownership of both pages. I own my own website outright, and I have access to my profile page on Twitter because I have an account there. (Incidentally, Kevin Marks has built a tool for distributed identity verification based on the reciprocal rel=“me” concept.)

Webmention Plugin

Next I downloaded and installed the Webmention plugin for WordPress. From the plugin interface, I just did a quick search, clicked install, then clicked “activate.” It’s really that easy.

It’s easy, but what does it do?

Webmention is an open internet protocol (recommended by the W3C) that allows any website to send and receive the equivalent of @mentions on the internet. Unlike sites like Twitter, Facebook, Medium, Google+, Instagram, etc. these mentions aren’t stuck within their own ecosystems, but actually work across website borders anywhere on the web that supports them.

The other small difference with webmention is instead of using one’s username (like @chrisaldrich in my case on Twitter) as a trigger, the trigger becomes the permalink URL you’re mentioning. In my case you can webmention either my domain name http://www.boffosocko.com or any other URL on my site. If you really wanted to, you could target even some of the smallest pieces of content on my website–including individual paragraphs, sentences, or even small sentence fragments–using fragmentions, but that’s something for another time.

Don’t use WordPress?

See if there’s webmention support for your CMS, or ask your CMS provider or community, system administrator, or favorite web developer to add it to your site based on the specification. While it’s nice to support both outgoing and incoming webmentions, for the use we’re outlining here, we only need to support incoming webmentions.

Connect Brid.gy

Sadly, I’ll report that Twitter does not support webmentions (yet?!) otherwise we could probably stop here and everything would work like magic. But they do have an open API right? “But wait a second now…” you say, “I don’t know code. I’m not a developer.”

Worry not, some brilliant engineers have created a bootstrap called Brid.gy that (among many other useful and brilliant things) forces silos like Twitter, Facebook, Google+, Instagram, and Flickr to send webmentions for you until they decide to support them natively. Better, it’s a free service, though you could donate to the ASPCA or EFF in their name to pay it forward.

So swing your way over to http://brid.gy and under “Get started” click on the Twitter logo. Use OAuth to log into Twitter and authorize the app. You’ll be redirected back to Brid.gy which will then ensure that your website and Twitter each have appropriate and requisite rel=“me”s on your links. You can then enable Brid.gy to “listen for responses.”

Now whenever anyone @mentions you (public tweets only) on Twitter, Brid.gy will be watching your account and will automatically format and send a webmention to your website on Twitter’s behalf.

On WordPress your site can send you simple email notifications by changing your settings in the Settings >> Discussion dashboard, typically at http://www.exampl.com/wp-admin/options-discussion.php. One can certainly use other plugins to arrange for different types of notifications as well.

Exotic Webmentions

A bonus step for those who want more control!

In the grand scheme of things webmentions are typically targeted at specific pages or posts on your site. General @mentions on Twitter not related to specific content on your site will usually be sent to your homepage. Over time, this may begin to get a bit overwhelming and may take your page longer to load as a result. An example of this is Kevin Marks’ site which has hundreds and hundreds of webmentions on it. What to do if this isn’t your preference?

In my case, I thought it would be wise to collect all these unspecific or general mentions on a special page on my site. I decided to call it “Mentions” and created a page at http://boffosocko.com/mentions/.

Update

While the code snippet just below should work, as of the 3.3.0 update of the Webmention Plugin, there is now an automatic setting at /wp-admin/options-discussion.php that will allow you to use a dropdown UI box to choose the page on your site to which homepage webmentions will be directed.

Then I inserted a small piece of custom code in the functions.php file of my site’s (child) theme like the following:

// For allowing exotic webmentions on homepages and archive pages

function handle_exotic_webmentions($id, $target) {

// If $id is homepage, reset to mentions page

if ($id == 55669927) {

return 55672667;

}

// do nothing if id is set

if ($id) {

return $id;

}

// return "default" id if plugin can't find a post/page

return 55672667;

}

add_filter("webmention_post_id", "handle_exotic_webmentions", 10, 2);

This simple filter for the WordPress Webmention plugin essentially looks at incoming webmentions and if they’re for a specific page/post, they get sent to that page/post. If they’re sent to either my homepage or aren’t directed to a particular page, then they get redirected to my /mentions/ page.

In my case above, my homepage has an id of 55669927 and my mentions page has an id of 55672667, you should change your numbers to the appropriate ids on your own site when using the code above. (Hint: these id numbers can usually be quickly found by hovering over the “edit” links typically found on such pages and posts and relying on the browser to show where they resolve.)

Tip of the Iceberg

Naturally this is only the tip of the indieweb iceberg. The indieweb movement is MUCH more than just this tiny, but useful, piece of functionality. There’s so much more you can do with not only Webmentions and even Brid.gy functionality. If you’ve come this far and are interested in more of how you can better own your online identity, connect to others, and own your data. Visit the Indieweb.org wiki homepage or try out their getting started page.

If you’re on WordPress, there’s some additional step-by-step instructions: Getting Started on WordPress.

I Love Webmentions

Want to have this yourself? Check out IndieWeb.org/WordPress, Webmention, and Brid.gy