I find that indexed subject headings can be useful for creating links between my wiki-like pages as well as links between atomic ideas in my digital zettelkasten. Gradually as one’s zettelkasten becomes larger and one works with it more, it becomes easier to recall individual ideas and cross link them. Until this happens or for smaller zettelkasten it can be useful to cross reference subject headings from one zettel to see what those link to and use those as a way to potential create links to other zettels. This method can also be used as a search/discovery aide for connecting edge ideas in new areas to pre-existing portions of one’s zettelkasten as well. Of course at massive scale with decades of work, I suspect this index will have increased value as well.

I don’t hear people talking about these types of indices for their zettelkasten in any of the influencer spaces or on social media. Are people simply skipping this valuable tool? For those enamored of Niklas Luhmann, we should mention that having and maintaining a subject index was a powerful portion of his system, even if the digitized version of his zettelkasten hasn’t yet been fully digitized. I haven’t seen the whole collection myself, but based on the condition of some of the cards in his index, Luhmann heavily used his subject index. (Note to self: I wonder what his whole system would look like in Obsidian?) Having a general key word/subject heading/topic heading index of all the material in one’s system can be very useful for general search and discovery as well. This is one of the reasons that John Locke wrote about a system for indexing one’s commonplace book in 1685. His work here is likely the distal reason Luhmann had one in his system.

Systems that have graphical knowledge graphs may make this process easier as one can look from one zettel out one or two levels to see where those link to.

Since such a large swath of my note taking practice starts by using Hypothes.is as my tool of choice, I’m able to leverage several years of using it to my benefit. Within it I’ve got 9,314 annotations, highlights, and bookmarks tagged with over 3,326 subject headings as of this writing.

To get all my subject heading tags, I used Jon Udell’s excellent facet tool to go to the tag editing interface. There I entered a “max” number larger than my total number of annotations and left the “tag” field empty to have it return the entire list of my tags. I was then able to edit a few of them to concatenate duplicates, fix misspellings, and remove some spurious tags.

An alternate way of doing this is to use a method described in this GitHub issue which shows how to get the tags out of local storage in your web browser. Your mileage may vary though if you use Hypothes.is in multiple browsers, which I do.

I moved this list from the tag editor into a spreadsheet software to massage the list a bit, clean up any character encodings, and then spit out a list of [[wikilinked]] index keywords. I then cut and pasted it into my notebook and threw in some alphabetical headings so that I could more easily jump around the list.

Now I’ve got an excellent tool and interface for more easily searching and browsing the various areas of my multi-purpose digital notebook.

I’m sure there are other methods within various tools of doing this, including searching all files and cutting and pasting those into a page, though in my case this doesn’t capture non-existing files. One might also try a search for a regex phrase like: /(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)\[\[(?:<\/\1>))|(?:\[\[))(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)(.+?)(?:<\/\2>))|(.+?))(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)\]\](?:<\/\5>))|(?:\]\]))/ (found here) or something as simple as /\[\[.*\]\]/ though in my case they don’t quite return what I really want or need.

I’ll likely keep using more local search and discovery, but perhaps having a centralized store of subject headings will offer some more interesting affordances for search and browsing?

Have you created an index for your system? How did you do it?

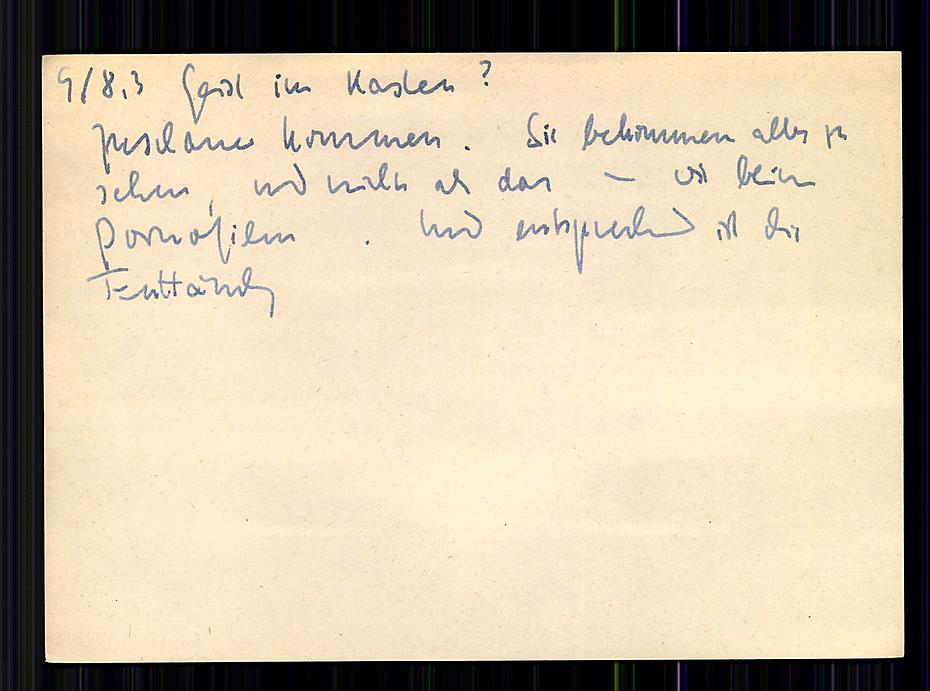

Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,

Niklas Luhmann, Zettelkasten II,