Image via Alexander Kluge/ Universität Bielefeld

Tag: Zettelkasten

Creating a commonplace book or zettelkasten index from Hypothes.is tags

I find that indexed subject headings can be useful for creating links between my wiki-like pages as well as links between atomic ideas in my digital zettelkasten. Gradually as one’s zettelkasten becomes larger and one works with it more, it becomes easier to recall individual ideas and cross link them. Until this happens or for smaller zettelkasten it can be useful to cross reference subject headings from one zettel to see what those link to and use those as a way to potential create links to other zettels. This method can also be used as a search/discovery aide for connecting edge ideas in new areas to pre-existing portions of one’s zettelkasten as well. Of course at massive scale with decades of work, I suspect this index will have increased value as well.

I don’t hear people talking about these types of indices for their zettelkasten in any of the influencer spaces or on social media. Are people simply skipping this valuable tool? For those enamored of Niklas Luhmann, we should mention that having and maintaining a subject index was a powerful portion of his system, even if the digitized version of his zettelkasten hasn’t yet been fully digitized. I haven’t seen the whole collection myself, but based on the condition of some of the cards in his index, Luhmann heavily used his subject index. (Note to self: I wonder what his whole system would look like in Obsidian?) Having a general key word/subject heading/topic heading index of all the material in one’s system can be very useful for general search and discovery as well. This is one of the reasons that John Locke wrote about a system for indexing one’s commonplace book in 1685. His work here is likely the distal reason Luhmann had one in his system.

Systems that have graphical knowledge graphs may make this process easier as one can look from one zettel out one or two levels to see where those link to.

Since such a large swath of my note taking practice starts by using Hypothes.is as my tool of choice, I’m able to leverage several years of using it to my benefit. Within it I’ve got 9,314 annotations, highlights, and bookmarks tagged with over 3,326 subject headings as of this writing.

To get all my subject heading tags, I used Jon Udell’s excellent facet tool to go to the tag editing interface. There I entered a “max” number larger than my total number of annotations and left the “tag” field empty to have it return the entire list of my tags. I was then able to edit a few of them to concatenate duplicates, fix misspellings, and remove some spurious tags.

An alternate way of doing this is to use a method described in this GitHub issue which shows how to get the tags out of local storage in your web browser. Your mileage may vary though if you use Hypothes.is in multiple browsers, which I do.

I moved this list from the tag editor into a spreadsheet software to massage the list a bit, clean up any character encodings, and then spit out a list of [[wikilinked]] index keywords. I then cut and pasted it into my notebook and threw in some alphabetical headings so that I could more easily jump around the list.

Now I’ve got an excellent tool and interface for more easily searching and browsing the various areas of my multi-purpose digital notebook.

I’m sure there are other methods within various tools of doing this, including searching all files and cutting and pasting those into a page, though in my case this doesn’t capture non-existing files. One might also try a search for a regex phrase like: /(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)\[\[(?:<\/\1>))|(?:\[\[))(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)(.+?)(?:<\/\2>))|(.+?))(?:(?:(?:<([^ ]+)(?:.*)>)\]\](?:<\/\5>))|(?:\]\]))/ (found here) or something as simple as /\[\[.*\]\]/ though in my case they don’t quite return what I really want or need.

I’ll likely keep using more local search and discovery, but perhaps having a centralized store of subject headings will offer some more interesting affordances for search and browsing?

Have you created an index for your system? How did you do it?

Other popular terms for such a system include Zettelkasten (meaning “slipbox” in German, coined by influential sociologist Niklas Luhmann), Memex (a word invented by American inventor Vannevar Bush), and digital garden (named by popular online creator Anne-Laure Le Cunff)

Please know that the zettelkasten and its traditions existed prior to Niklas Luhmann. He neither invented them nor coined their name. It’s a commonly repeated myth on the internet that he did and there’s ample evidence of their extensive use prior to his well known example. I’ve documented some brief history on Wikipedia to this effect should you need it: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zettelkasten

The earliest concept of a digital garden stems from Mark Bernstein’s essay Hypertext Gardens: Delightful Vistas in 1998. This torch was picked up by academic Mike Caulfield in a 2015 keynote/article The Garden and The Stream: A Technopastoral.

Anne-Laure Le Cunff’s first mention of “digital garden” was on April 21, 2020

Progress on my digital garden / evergreen notebook inspired by @andy_matuschak🌱

Super grateful for @alyssaxuu who’s been literally handholding me through the whole thing — thank you! pic.twitter.com/ErzvEsdAUj

— Anne-Laure Le Cunff (@anthilemoon) April 22, 2020

Which occurred just after Maggie Appleton’s mention on 2020-04-15

Nerding hard on digital gardens, personal wikis, and experimental knowledge systems with @_jonesian today.

We have an epic collection going, check these out…

1. @tomcritchlow‘s Wikifolders: https://t.co/QnXw0vzbMG pic.twitter.com/9ri6g9hD93

— Maggie Appleton 🧭 (@Mappletons) April 15, 2020

And several days after Justin Tadlock’s article on 2020-04-17

Before this there was Joel Hooks by at least 2020-02-04 , though he had been thinking about it in late 2019.

He was predated by Tom Critchlow on 2018-10-18 who credits Mike Caulfield’s article from 2015-10-17 as an influence.

Archive.org has versions of the phrase going back into the early 2000’s: https://web.archive.org/web/*/%22digital%20garden%22

Hopefully you’re able to make the edits prior to publication, or at least in an available errata.

Most often we privilege the chronological time order because that’s how we ourselves live them, write them, and how much of our audience experiences them.

But consider looking at someone’s note collections or zettelkasten after they’re gone? One wouldn’t necessarily read them in physical order or even attempt to recreate them into time-based order. Instead they’d find an interesting topical heading, delve in and start following links around.

I’ve been thinking about this idea of “card index (or zettelkasten) as autobiography” for a bit now, though I’m yet to come to any final conclusions. (References and examples see also: https://hypothes.is/users/chrisaldrich?q=%22card+index+as+autobiography%22).

I’ve also been looking at Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project which is based on a chunk of his (unfinished) zettelkasten notes which editors have gone through and published as books. There were many paths an editor could have taken to write such a book, and many of them that Benjamin himself may not have taken, but there it is at the end of the day, a book ostensibly similar to what Benjamin would have written because there it is in his own writing in his card index.

After his death, editors excerpted 330 index cards of Roland Barthes’ collection of 12,000+ about his reactions to the passing of his mother and published them in book form as a perceived “diary”. What if someone were to do this with your Tweets or status updates after your death?

Does this perspective change your ideas on time ordering, taxonomies, etc. and how people will think about what we wrote?

I’ll come back perhaps after I’ve read Barthes’ The Death of the Author…

Also in reply to:

https://www.zotero.org/groups/4676190/tools_for_thought

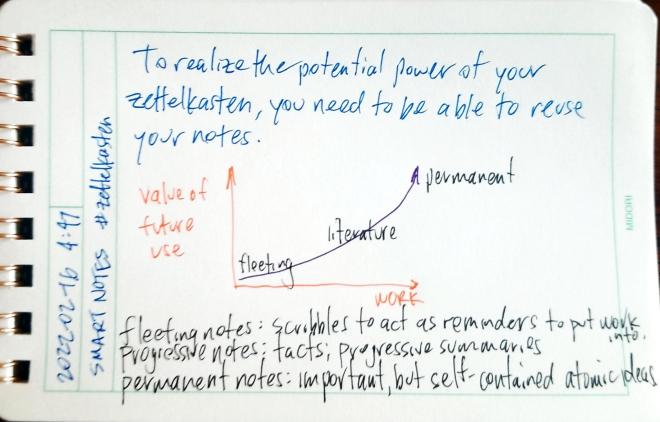

The most detailed form of the idea can be found in Sönke Ahrens’ book How to Take Smart Notes, which also looks closely at much of the note taking and psychology related research over the past several decades. While he frames the method in terms of writing and creation as the end goal, much of the method dovetails with Bloom’s Taxonomy as I’ve outlined. It could also be framed as Cornell Notes with a greater focus on atomic notes that are highly linked and thereby integrating a student’s new knowledge with their prior knowledge.

I’d love to see more educators scaffolding the use of this note taking tool in their classes, especially in high school and undergraduate education.

Cross reference: https://boffosocko.com/tag/note-taking/

The Zettelkasten Method of Note Taking Mirrors Most of the Levels of Bloom’s Taxonomy

Recall briefly that Bloom’s Taxonomy levels can be summarized as: remember, understand, apply, analyze, evaluate, and create.

Outlining the similarities

One needs to be able to generally understand an idea(s) to be able to write it down clearly in one’s own words. This is parallel to creating literature notes as one reads. Gaps in one’s understanding will be readily apparent when one realizes that they’re not able to explain an idea simply and clearly.

Regular work within a zettelkasten helps to reinforce memory of ideas for understanding, long term retention, and the ability to easily remember them. Many forms of zettelkasten software have functionality for direct spaced repetition if not dovetails for spaced repetition software like Anki or Mnemosyne.

Applying the knowledge to other situations happens almost naturally with the combinatorial creativity that occurs within a zettelkasten. Raymundus Llullus would be highly jealous here I think.

Analysis is heavily encouraged as one takes new information and actively links it to prior knowledge and ideas; this is also concurrent with the application of knowledge.

Being able to compare and contrast two ideas on separate cards is also part of the analysis portions of Bloom’s taxonomy which also leads into the evaluation phase. Is one idea better than another? How do they dovetail? How might they create new knowledge? Juxtaposed ideas cry out for evaluation.

Finally, as argued by Ahrens, one of the most important reasons for keeping a zettelkasten is to use it to generate or create new ideas and thoughts and then use the zettelkasten as a tool to synthesize them in articles, books, or other media in a clear and justified manner.

Other examples?

I’m curious to hear if any educators have used the zettelkasten framing specifically for scaffolding the learning process for their students? There are some seeds of this in the social annotation space with tools like Diigo and Hypothes.is, but has anyone specifically brought the framing into their classes?

I’ve seen a few examples of people thinking in this direction and even @CalHistorian specifically framing things this way, but I’m curious to hear about other actual experiences in the field.

The history of the recommendation and use of commonplace books in education is long and rich (Erasmus, Melanchthon, Agricola, et al.), until it began disappearing in the early 20th century. I’ve seen a few modern teachers suggesting commonplaces, but have yet to run across others suggesting zettelkasten until Ahrens’ book, which isn’t yet widespread, at least in the English speaking world. And even in Ahrens’ case, his framing is geared specifically to writing more so than general learning and education.

Featured image courtesy of Vanderbilt University Center for Teaching (CC BY 2.0

Contextualizing Cornell Notes in the Note Taking Traditions

Cornell notes come from a time closer to the traditional space of commonplace books, academic thinking, and note taking that was more prevalent in the early 1900’s and from which also sprang the zettelkasten tradition. I can’t help but be reminded that the 10th edition of Pauk’s book How to Study in College (Wadsworth, 2011, p.394), which helped to popularize the idea of Cornell notes with the first edition in 1962, literally ends the book with the relationship of the word ‘topic’ by way of Greek to the Latin ‘loci communes‘ (commonplaces), though it’s worth bearing in mind that it contains no discussion of the commonplace book or its long tradition in our intellectual history.

One was meant to use Cornell notes to capture broad basic ideas and facts (fleeting notes) and things to follow up on for additional research or work. Then they were meant to be revisited to focus on creating questions that might be used for spaced repetition, a research space that has seen tremendous growth and advancement since the simpler times in which the Cornell note taking method was designed.

Additionally one was meant to revisit their notes to draw out the most salient points and ideas. This is part of the practice of taking the original ideas and writing them out clearly in one’s own words to improve one’s understanding of the material. Within a zettelkasten framing, this secondary review is part of the process of creating future useful literature notes or permanent notes that one might also re-use in their future writing and thinking.

Missing from the Cornell notes practice but more directly centered in the zettelkasten practice is taking one’s notes and directly linking them to other related thoughts in one’s system. This places this method closer to the commonplace book tradition than the zettelkasten tradition.

While a more basic and naïve understanding of Cornell notes in current academic environments still works on many levels, students and active researchers might be better advised to look at their practices in view of broader framings like that of Sönke Ahrens’s book How to Take Smart Notes: One Simple Technique to Boost Writing, Learning and Thinking.

It also bears noting that one could view the first stage of Cornell notes in light of the practice of keeping a waste book and then later transferring their more permanent and better formed ideas into their commonplace book.

Similarly one might also view full sheets of finished Cornell notes as permanent notes mixed in amidst fleeting notes and held together on pages rather than individual cards. This practice sounds somewhat similar in structure to Sönke Ahrens’s use of Roam Research to compile multiple related ideas in individually linked blocks on a single page holding them together in a pseudo-project page for more immediate and potentially specific future use.

I’ve got lots of stuff to say, I’m just saving it all up.

—Beca Mitchell, Pitch Perfect 2

Do you suppose she’s using a zettelkasten or simply “stacking ammo” like Eminem?

https://niklas-luhmann-archiv.de/bestand/zettelkasten/zettel/ZK_2_NB_9-8g_V