Category: note taking

First Use of Zettelkasten in an English Language Setting?

But here’s a fun little historical linguistic puzzle:

What was the first use of the word Zettelkasten in a predominantly English language setting?

In my own notes/research the first occurrence I’ve been able to identify in an English language setting is on Manfred Kuehn’s blog in Taking note: Luhmann’s Zettelkasten on 2007-12-16. He’d just started his blog earlier that month.

Has anyone seen an earlier usage? Can you find one? Can you beat this December 2007 date or something close by a different author?

Google’s nGram Viewer doesn’t indicate any instances of it from 1800-2019 in its English search, though does provide a graph for German with peaks in the 1850s, 1892 (just after Ernst Bernheim’s Lehrbuch der Historischen Methode in 1889), 1912, 1925, and again in 1991.

Twitter search from 2006-2007 finds nothing and there are only two results in German both mentioning Luhmann.

My best guess for earlier versions of the appearance zettelkasten in English might stem from the work/publications of S. D. Goitein or Gotthard Deutsch, but I’ve yet to see anything there.

For those who speak German, what might you posit as a motivating source for the rise of the word in the 1850s or any of the other later peaks?

The Adjustable Table Company of Grand Rapids, Michigan manufactured a combination table for both telephones and index cards. It was designed as an accessory to be stood next to one’s desk to accommodate a telephone at the beginning of the telephone era and also served as storage for one’s card index.

Given the broad business-based use of the card index at the time and the newness of the telephone, this piece of furniture likely was not designed as an early proto-rolodex, though it certainly could have been (and very well may have likely been) used as such in practice.

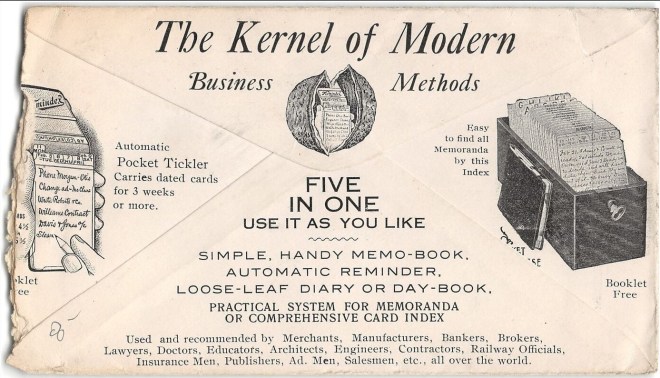

The Memindex Method: an early precursor of the Memex, Hipster PDA, 43 Folders, GTD, BaSB, and Bullet Journal systems

Wilson Memindex Co., Rochester, NY

It was fascinating to run across the Memindex, a productivity tool from the Wilson Memindex Co., advertised in a December 1906 issue of System: The Magazine of Business. Memindex seems to be an obvious portmanteau of the words memory and index.

Let YOUR MIND GO FREE

Do not tax your brain trying to remember. Get the MEMINDEX HABIT and you can FORGET WITH IMPUNITY. An ideal reminder and handy system for keeping all memoranda where they will appear at the right time. Saves time, money, opportunity. A brain saver. No other device answers its purpose. A Great Help for Busy Men, Used and recommended by Bankers, Manufacturers, Salesmen, Lawyers, Doctors, Merchants, Insurance Men, Architects, Educators, Contractors, Railway Managers Engineers, Ministers, etc., all over the world. Order now and get ready to Begin the New Year Right. Rest of ’06 free with each outfit. Express prepaid on receipt of price. Personal checks accepted.

Also a valuable card index for desk use. Dated cards from tray are carried in the handy pocket case, 2 to 4 weeks at a time. To-day’s card always at the front. No leaves to turn. Helps you to PLAN YOUR WORK WORK YOUR PLAN ACCOMPLISH MORE You need it. Three years’ sales show that most all business and professional men need it. GET IT NOW. WILSON MEMINDEX CO. 93 Mills St., Rochester, N. Y.

Early Computer Science Influence?

The Memindex product appears several decades prior to Vannevar Bush’s “coinage” of memex in As We May Think (The Atlantic, July 1945). While many credit Bush for an early instantiation of the internet using the model of a desk, microfiche, and a filing system, almost all of these moving parts had already existed in late 19th century networked office furniture and were just waiting for automation and computerization. The primary difference in this Memindex card system and Bush’s Memex is the higher information density made available through the use of microfiche. Now it turns out his coinage of memex appears to have been in the zeitgeist decades prior as well. I’ve got evidence that the Wilson Memindex was sold well into the early 1950s. (My current dating is to 1952, though later examples may exist.) Below I’ve pictured some cards from the same year as Bush’s now famous piece in the Atlantic.

Most people are more familiar with the popular 20th century magazine System than they realize. Created and published by A. W Shaw, one of the partners of Shaw-Walker, a major manufacturer of office furniture in the early 20th century, the popular magazine was sold to McGraw-Hill Company in 1927/8 and renamed Businessweek which was later sold again and renamed Bloomberg Businessweek.

Relationship to other modern productivity methods

Some will certainly see close ties of this early product to the idea of the “hipster PDA” or Hawk Sugano’s Pile of Index Cards which appeared in 2006. It also doesn’t take much imagination for one to look at the back of a Wilson Memindex envelope from 1909 or an ad from the 1930s to see the similarity to the 43 folders system, bits of Getting Things Done (GTD), or the Bullet Journal methods in common use today. The 1909 envelope also appears to combine a predecessor to the 43 folders idea mixed with the hipster PDA in a coherent pocket and desk-based system.

With alphabetic tabs for the desktop version, one could easily have used this for “Building a Second Brain” as described by modern productivity gurus who almost exclusively suggest digital tools for maintaining their systems now. The 1909 envelop specifically recommends using the system as “comprehensive card index” which is essentially what most second brain or zettelkasten systems are, though there is a broad disconnect between some of this and the reimagining of the zettelkasten in current craze for using Niklas Luhmann-esque organization methods which have some different aims.

What’s interesting beyond the similarities of the systems is the means by which they were sold and spread. Older systems like the Memindex or related general office filing and indexing systems (Shaw-Walker), were primarily selling physical products/hardware like boxes, filing cabinets, holders, cards, and dividers as much as they were selling a process or idea. Mid- and late-century companies like Day-Timer or FranklinCovey also sold physical stationery products (calendars, planners, boxes, binders, books, ) but also began more heavily selling ideas like “productivity” and “leadership”. Modern productivity gurus are generally selling the ideas of the systems and making their money not on the physical items, software or programs which implement them, but with consulting fees, class fees, subscriptions, books which describe their systems, or even advertising against page or video views.

The 1906 version of the Memindex was popular enough to already be offered with the following options of materials for the distinguishing tastes of consumers:

- Cowhide Seal Leather Case and hardwood tray

- Am. Russia Leather Case and plain oak tray

- Genuine Morocco Case and quartered oak tray

What options is your current productivity guru or system offering? What are the differentiations and affordances it’s offering compared to similar systems in the early 1900s? Where is the “rich Corinthian leather“?

The Memindex Method

The basic Memindex method consists of using 2 3/4″ x 4 1/2″ (vest pocket sized) or 3 x 5 1/2″ cards depending on one’s size preference to jot down to do lists or tickler items on individually dated cards which are kept in a desk-based wooden card index with tabs for both months as well as alphabetic tabs in some systems. One then keeps a small pocket-sized card holder with the coming three weeks’ worth of cards on their person for active daily use and files them away as the days go by.

Apparently the truism “everything old is new again” is true yet again.

Rules against quotes in Zettelkasten? A closer look at Ahrens on Quotes and Collecting

The word “quote” (or close variations like “quotes” and “quotation(s)”) only appear 19 times in the first edition of Ahrens’ book.

In most of the contexts which have what one might call an “anti-quote” connotation, he’s directly recommending against the practice of indiscriminate highlighting/excerpting and collecting of general quotes specifically because they don’t aid in creating understanding by the reader. Instead he repeatedly recommends that one internalize the information by rewriting it in their own words instead. This helps the reader to better understand and know what the author is trying to convey. This also allows the reader to have material in their collection already written in their own words for later reuse.

Talking about “literature notes” Ahrens writes:

He did not just copy ideas or quotes from the texts he [Luhmann] read, but made a transition from one context to another.

Be extra selective with quotes – don’t copy them to skip the step of really understanding what they mean. Keep these notes together with the bibliographic details in one place – your reference system.

Places where quote appears in a context which argues against indiscriminate collection of quotes:

A typical mistake is made by many diligent students who are adhering to the advice to keep a scientific journal. A friend of mine does not let any idea, interesting finding or quote he stumbles upon dwindle away and writes everything down.

As well, the mere copying of quotes almost always changes their meaning by stripping them out of context, even though the words aren’t changed. This is a common beginner mistake, which can only lead to a patchwork of ideas, but never a coherent thought.

It is so much easier to develop an interesting text from a lively discussion with a lot of pros and cons than from a collection of one-sided notes and seemingly fitting quotes

Even doctoral students sometimes just collect de-contextualised quotes from a text – probably the worst possible approach to research imaginable.

It is not surprising, therefore, that Lonka recommends what Luhmann recommends: Writing brief accounts on the main ideas of a text instead of collecting quotes.

Now let’s take a quick look at some of Ahrens’ “pro quote” passages which provide the opposite view of when and where quotes can be useful:

The available books fall roughly into two categories. The first teaches the formal requirements: style, structure or how to quote correctly.

It would certainly make things a lot easier if you already had everything you need right in front of you: The ideas, the arguments, the quotes, long developed passages, complete with bibliography and references.

You follow up on a footnote, go back to research and might add a fitting quote to one of your papers in the making.

In this textual infrastructure, this so-often taught workflow, it indeed does not make much sense to rewrite these notes and put them into a box, only to take them out again later when a certain quote or reference is needed during writing and thinking.

How is one to have useful/impactful/fitting/necessary quotes at hand if they haven’t excerpted them as they read? In these portions he is actively suggesting that quotes from one’s reading in their notes can be a good thing and can help in making persuasive arguments. The secret is that they need to be done judiciously. One needs to be able to quote in a manner which keeps the original context and argument, but which can also fit into your current context and provide support or further argumentation.

As an example of terrible decontextualization, who hasn’t attended a wedding that featured a reading of 1 Corinthians 13? The passage seems wholly appropriate for a church wedding reading, but when you consider that it’s excerpted out of context you might reconsider using it at your own wedding. Go back and try reading it in light of being sandwiched between Corinthians 12 and 14 and you’ll change your mind that chapter 13 is about the sort of romantic love and implied by a wedding. Once you’ve done this, there’s added comedic subtext to scenes like the following from Wedding Crashers (New Line Cinema, 2005):

Father O’Neil: And now for our second reading I’d like to ask the bride’s sister Gloria up to the lectern.

John Beckwith: 20 bucks First Corinthians.

Jeremy Grey: Double or nothing Colossians 3:12.

Gloria Cleary: And now a reading from Paul’s first letter to the Corinthians.

To prevent embarrassment of this sort, perhaps when you’re quoting a source directly you ought to provide at least a short note about the context in which the words were provided?

Any good rhetorician will tell you that quoting works in your writing can be incredibly helpful in building context and creating authority.

If anything, Ahrens’ book is missing a section on “how to quote correctly”, and this is a stumbling block of his text. As a quick remedy, one could read a bit of Seneca perhaps?

“We should follow, men say, the example of the bees, who flit about and cull the flowers that are suitable for producing honey, and then arrange and assort in their cells all that they have brought in; these bees, as our Vergil says: ‘pack close the flowering honey And swell their cells with nectar sweet.’”

—Seneca in 84th letter to Luculius (“On Gathering Ideas”), Epistles 66-92. With an English translation by Richard G. Gummere. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press (Loeb Classical Library, 2006), 277-285.

Beyond just Ahrens there are several thousands of years of prior art seen in the commonplace book tradition where quotes feature not only prominently but at times almost exclusively. Quotes, particularly sententiae, are some of the most excerpted and transmitted bits of knowledge in the entire Western canon. Without quotes, the entire tradition of excerpting and note taking might not exist.

Of course properly quoting is a sub-art in and of itself within rhetoric and the ars excerpendi.

Fellow note taking writer Umberto Eco warns against this same sort of indiscriminate collecting without actively making the knowledge your own. In How to Write a Thesis (MIT Press, 2015, p125), instead of railing against indiscriminate highlighting, or digital cutting and pasting, Eco talks about another sort of technological collection tool more rampant in the 1990s and early 2000s which facilitated this sort of pattern: the photocopier.

Beware the “alibi of photocopies”! Photocopies are indispensable instruments. They allow you to keep with you a text you have already read in the library, and to take home a text you have not read yet. But a set of photocopies can become an alibi. A student makes hundreds of pages of photocopies and takes them home, and the manual labor he exercises in doing so gives him the impression that he possesses the work. Owning the photocopies exempts the student from actually reading them. This sort of vertigo of accumulation, a neocapitalism of information, happens to many. Defend yourself from this trap: as soon as you have the photocopy, read it and annotate it immediately. If you are not in a great hurry, do not photocopy something new before you own (that is, before you have read and annotated) the previous set of photocopies. There are many things that I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it.

Many people may highlight, tag, or collect a variety of quotes within a text, but this activity is only a simulacrum of understanding and knowledge acquisition. This pattern can be particularly egregious in digital contexts where cutting and pasting has be come even easier and simpler than using a photocopier. Writing it down and summarizing important ideas in your own words will actively help you on your way to ownership of the material you’re consuming.

A zettelkasten with no quotes—by definition—shouldn’t carry the name. So let’s lay to rest that dreadful idea that quotes aren’t allowed in a zettelkasten.

And if you’re just starting out on your zettelkasten or commonplace book journey and don’t know where to begin, I’ve recommended before writing down the following apropos quote and continuing from there:

No piece of information is superior to any other. Power lies in having them all on file and then finding the connections. There are always connections; you have only to want to find them.

—Umberto Eco, Foucault’s Pendulum (Secker & Warburg)

Once combined via linking, further thinking and writing, they can be released as novel ideas for everyone to use.

On the Jokerzettel: An Apocalyptic Interpretation of Luhmann’s note ZKII 9/8j

Niklas Luhmann’s Jokerzettel 9/8j

Many have asked about the meaning of Niklas Luhmann’s so-called jokerzettel over the past several years.

9/8j Im Zettelkasten ist ein Zettel, der das

Argument enthält, das die Behauptungen

auf allen anderen Zetteln widerlegt.Aber dieser Zettel verschwindet, sobald man

den Zettelkasten aufzieht.

D.h. er nimmt eine andere Nummer an,

verstellt sich und ist dann nicht zu finden.Ein Joker.

—Niklas Luhmann, ZK II: Zettel 9/8j

Translation:

9/8j In the slip box is a slip containing the argument that refutes the claims on all the other slips. But this slip disappears as soon as you open the slip box. That is, he assumes a different number, disguises himself and then cannot be found. A joker.

An Apocalyptic Interpretation

Here’s my slightly extended interpretation, based on my own practice with several thousands of cards, about what Luhmann meant:

Imagine you’ve spent your life making and collecting notes and ideas and placing them lovingly on index cards. You’ve made tens of thousands and they’re a major part of your daily workflow and support your life’s work. They define you and how you think. You agree with Friedrich Nietzsche’s concession to Heinrich Köselitz that “You are right — our writing tools take part in the forming of our thoughts.” Your time is alive with McLuhan’s idea that “The medium is the message.” or his friend John Culkin‘s aphorism, “We shape our tools and thereafter they shape us.”

Eventually you’re going to worry about accidentally throwing your cards away, people stealing or copying them, fires (oh! the fires), floods, or other natural disasters. You don’t have the ability to do digital back ups yet. You may ask yourself, can I truly trust my spouse not to destroy them? What about accidents like dropping them all over the floor and needing to reorganize them or worse, what if the ghost in the machine should rear its head?

You’ll fear the worst, but the worst only grows logarithmically in proportion to your collection.

Eventually you pass on opportunities elsewhere because you’re worried about moving your ever-growing collection. What if the war should obliterate your work? Maybe you should take them into the war with you, because you can’t bear to be apart?

If you grow up at a time when Schrödinger’s cat is in the zeitgeist, you’re definitely going to have nightmares that what’s written on your cards could horrifyingly change every time you look at them. Worse, knowing about the Heisenberg Uncertainly Principle, you’re deathly afraid that there might be cards, like electrons, which are always changing position in ways you’ll never be able to know or predict.

As a systems theorist, you view your own note taking system as a input/output machine. Then you see Claude Shannon’s “useless machine” (based on an idea of Marvin Minsky) whose only function is to switch itself off. You become horrified with the idea that the knowledge machine you’ve painstakingly built and have documented the ways it acts as an independent thought partner may somehow become self-aware and shut itself off!?!

And worst of all, on top of all this, all your hard work, effort, and untold hours of sweat creating thousands of cards will be wiped away by a potential unknowable single bit of information on a lone, malicious card; your only recourse is suicide, the unfortunate victim of dataism.

Of course, if you somehow manage to overcome the hurdle of suicidal thoughts, and your collection keeps growing without bound, then you’re sure to die in a torrential whirlwind avalanche of information and cards, literally done in by information overload.

But, not wishing to admit any of this, much less all of this, you imagine a simple trickster, a joker, something silly. You write it down on yet another card and you file it away into the box, linked only to the card in front of it, the end of a short line of cards with nothing following it, because what could follow it? Put it out of your mind and hope your fears disappear away with it, lost in your box like the jokerzettel you imagined. You do this with a self-assured confidence that this way of making sense of the world works well for you, and you settle back into the methodical work of reading and writing, intent on making your next thousands of cards.

Zettelkasten Face Off: Niklas Luhmann vs S.D. Goitein

On The Interdisciplinarity of Zettelkasten: Card Numbering, Topical Headings, and Indices

If you feel the need to categorize and separate them in such a surgical fashion, then let your index be the place where this happens. This is what indices are for! Put the locations into the index to create the semantic separation. Math related material gets indexed under “M” and history under “H”. Now those ideas can be mixed up in your box, but they’re still findable. DO NOT USE OR CONSIDER YOUR NUMBERS AS TOPICAL HEADINGS!!! Don’t make the fatal mistake of thinking this. The numbers are just that, numbers. They are there solely for you to be able to easily find the geographic location of individual cards quickly or perhaps recreate an order if you remove and mix a bunch for fun or (heaven forfend) accidentally tip your box out onto the floor. Each part has of the system has its job: the numbers allow you to find things where you expect them to be and the index does the work of tracking and separating topics if you need that.

The broader zettelkasten, tools for thought, and creativity community does a terrible job of explaining the “why” portion of what is going on here with respect to Luhmann’s set up. Your zettelkasten is a crucible of ideas placed in juxtaposition with each other. Traversing through them and allowing them to collide in interesting and random ways is part of what will create a pre-programmed serendipity, surprise, and combinatorial creativity for your ideas. They help you to become more fruitful, inventive, and creative.

Broadly the same thing is happening with respect to the structure of commonplace books. There one needs to do more work of randomly reading through and revisiting portions to cause the work or serendipity and admixture, but the end results are roughly the same. With a Luhmann-esque zettelkasten, it’s a bit easier for your favorite ideas to accumulate into one place (or neighborhood) for easier growth because you can move them around and juxtapose them as you add them rather than traversing from page 57 in one notebook to page 532 in another.

If you use your numbers as topical or category headings you’ll artificially create dreadful neighborhoods for your ideas to live in. You want a diversity of ideas mixing together to create new ideas. To get a sense of this visually, play the game Parable of the Polygons in which one categorizes and separates (or doesn’t) triangles and squares. The game created by Vi Hart and Nicky Case based on the research of Thomas Schelling (Dynamic Models of Segregation, 1971) provides a solid and visual example of the sort of statistical mechanics going on with ideas in your zettelkasten when they’re categorized rigidly. If you rigidly categorize ideas and separate them, you’ll drastically minimize the chance of creating the sort of useful serendipity of intermixed and innovative ideas. A zettelkasten isn’t simply the aggregation repository many use it for—it’s a rumination device, a serendipity engine, a creativity accelerator. To get the best and most of this effect, one must carefully help to structure their card index to generate it.

It’s much harder to know what happens when you mix anthropology with complexity theory if they’re in separate parts of your mental library, but if those are the things that get you going, then definitely put them right next to each other in your slip box. See what happens. If they’re interesting and useful and they’ve got explicit numerical locators and are cross referenced in your index, they are unlikely to get lost. Be experimental occasionally. Don’t put that card on Henry David Thoreau in the section on writers, nature, or Concord, Massachusetts—especially if those aren’t interesting to you. Besides, everyone has already worn down those associative trails, paved them, and re-paved them. Instead put him next to your work on innovation and pencils because it’s much easier to become a writer, philosopher, and intellectual when your family’s successful pencil manufacturing business can pay for you to attend Harvard and your house was always full of writing instruments from a young age. Now you’ve got something interesting and creative. (And if you really must, you can always link the card numerically to the other transcendentalists across the way.)

In case they didn’t hear it in the back, I’ll shout it again:

ACTIVELY WORK AGAINST YOUR NATURAL URGE TO USE YOUR ZETTELKASTEN NUMBERS AS TOPICAL HEADINGS! MIX IT UP INSTEAD.

Featured image by Michael Treu from Pixabay

A note about my article on Goitein with respect to Zettelkasten Output Processes

I’m hoping that this example will give the aspiring interested note takers, commonplacers, and zettelkasten maintainers a peek into a small portion of my own specific process if they’d like to look more closely at such an example.

Following the reading and note taking portions of the process, I spent about 5 minutes scratching out a brief outline for the shape of the piece onto one of my own 4 x 6″ index cards. I then spent 15 minutes cutting and pasting all of what I felt the relevant notes were into the outline and arranging them. I then spent about two hours writing and (mostly) editing the whole. In a few cases I also cut and pasted a few things from my digital notes which I also felt would be interesting or relevant (primarily the parts on “notes per day” which I had from prior research.) All of this was followed by about an hour on administrivia like references and HTML formatting to put it up on my website. While some portions were pre-linked in a Luhmann-ese zettelkasten sense, other portions like the section on notes per day were a search for that tag in my digital repository in Hypothes.is which allowed me to pick and choose the segments I wanted to cut and paste for this particular piece.

From the outline to the finished piece I spent about three and a half hours to put together the 3,500 word piece. The research, reading, and note taking portion took less than a day’s worth of entertaining diversion to do including several fun, but ultimately blind alleys which didn’t ultimately make the final cut.

For the college paper writers, this entire process took less than three days off and on to produce what would be the rough equivalent of a double spaced 15 page paper with footnotes and references. Naturally some of my material came from older prior notes, and I would never suggest one try to cram write a paper this way. However, making notes on a variety of related readings over the span of a quarter or semester in this way could certainly allow one to relatively quickly generate some reasonably interesting material in a way that’s both interesting to and potentially even fun for the student and which could potentially push the edges of a discipline—I was certainly never bored during the process other than some of the droller portions of cutting/pasting.

While the majority of the article is broadly straightforward stringing together of facts, one of the interesting insights for me was connecting a broader range of idiosyncratic note taking and writing practices together across time and space to the idea of statistical mechanics. This is slowly adding to a broader thesis I’m developing about the evolving life of these knowledge practices over time. I can’t wait to see what develops from this next.

In the meanwhile, I’m happy to have some additional documentation for another prominent zettelkasten example which resulted in a body of academic writing which exceeds the output of Niklas Luhmann’s own corpus of work. The other outliers in the example include a significant contribution to a posthumously published book as well as digitized collection which is still actively used by scholars for its content rather than for its shape. I’ll also note that along the way I found at least one and possibly two other significant zettelkasten examples to take a look at in the near future. The assured one has over 15,000 slips, apparently with a hierarchical structure and a focus on linguistics which has some of the vibes of John Murray’s “slip boxes” used in the creation of the Oxford English Dictionary.

S.D. Goitein’s Card Index (or Zettelkasten)

Abstract

Scholar and historian S.D. Goitein built and maintained a significant collection of over 27,000 notes in the form of a card index (or zettelkasten1) which he used to fuel his research and academic writing output in the mid to late twentieth century. The collection was arranged broadly by topical categories and followed in the commonplace book tradition though it was maintained on index cards. Uncommon to the space, his card index file was used by subsequent scholars for their own research and was ultimately digitized by the Princeton Geniza Project.

Introduction to S.D. Goitein and his work

Shelomo Dov Goitein (1900-1985) was a German-Jewish historian, ethnographer, educator, linguist, Orientalist, and Arabist who is best known for his research and work on the documents and fragments from the Cairo Geniza, a fragmented collection of some 400,000 manuscript fragments written between the 6th and 19th centuries.

Born in Burgkunstadt, Germany in 1900 to a line of rabbis, he received both a secular and a Talmudic education. At the University of Frankfurt he studied both Arabic and Islam from 1918-1923 under Josef Horovitz and ultimately produced a dissertation on prayer in Islam. An early Zionist activist, he immigrated to Palestine where he spent 34 years lecturing and teaching in what is now Israel. In order to focus his work on the Cairo Geniza, he moved to Philadelphia in 1957 where he lived until he died on February 6, 1985.

After becoming aware of the Cairo Geniza’s contents, S.D. Goitein ultimately devoted the last part of his life to its study. The Geniza, or storeroom, at the Ben Ezra Synagogue was discovered to hold manuscript fragments made of vellum, paper, papyrus, and cloth and written in Hebrew, Arabic, and Aramaic covering a wide period of Middle Eastern, North African, and Andalusian Jewish history. One of the most diverse collections of medieval manuscripts in the world, we now know it provides a spectacular picture of cultural, legal, and economic life in the Mediterranean particularly between the 10th and the 13th centuries. Ultimately the collection was removed from the Synagogue and large portions are now held by a handful of major research universities and academic institutes as well as some in private hands. It was the richness and diversity of the collection which drew Goitein to study it for over three decades.

Research Areas

Goitein’s early work was in Arabic and Islamic studies and he did a fair amount of work with respect to the Yemeni Jews before focusing on the Geniza.

As a classically trained German historian, he assuredly would have been aware of the extant and growing popularity of the historical method and historiography delineated by the influential works of Ernst Bernheim (1899) and Charles Victor Langlois and Charles Seignobos (1898) which had heavily permeated the areas of history, sociology, anthropology, and the humanities by the late teens and early 1920s when Goitein was at university.

Perhaps as all young writers must, in the 1920s Goitein published his one and only play Pulcellina about a Jewish woman who was burned at the stake in France in 1171. [@NationalLibraryofIsrael2021] # It is unknown if he may have used a card index method to compose it in the way that Vladimir Nabokov wrote his fiction.

Following his move to America, Goitein’s Mediterranean Society project spanned from 1967-1988 with the last volume published three years after his death. The entirety of the project was undertaken at the University of Pennsylvania and the Institute for Advanced Study to which he was attached. # As an indicator for its influence on the area of Geniza studies, historian Oded Zinger clearly states in his primer on research material for the field:

The first place to start any search for Geniza documents is A Mediterranean Society by S. D. Goitein. [@Zinger2019] #

Further gilding his influence as a historian is a quote from one of his students:

You know very well the verse on Tabari that says: ‘You wrote history with such zeal that you have become history yourself.’ Although in your modesty you would deny it, we suggest that his couplet applies to yourself as well.”

—Norman Stillman to S.D. Goitein in letter dated 1977-07-20 [@NationalLibraryofIsrael2021] #

In the early days of his Mediterranean Society project, he was funded by the great French Historian Fernand Braudel (1902-1985) who also specialized on the Mediterranean. Braudel had created a center in Paris which was often referred to as a laboratoire de recherches historiques. Goitein adopted this “lab” concept for his own work in American, and it ultimately spawned what is now called the Princeton Geniza Lab. [@PrincetonGenizaLab] #

The Card Index

Basics

In addition to the primary fragment sources he used from the Geniza, Goitein’s primary work tool was his card index in which he ultimately accumulated more than 27,000 index cards in his research work over the span of 35 years. [@Rustow2022] # Goitein’s zettelkasten ultimately consisted of twenty-six drawers of material, which is now housed at the National Library of Israel. [@Zinger2019] #.

Goitein’s card index can broadly be broken up into two broad collections based on both their contents and card sizes:

- Approximately 20,000 3 x 5 inch index cards2 are notes covering individual topics generally making of the form of a commonplace book using index cards rather than books or notebooks.

- Over 7,000 5 x 8 inch index cards which contain descriptions of a fragment from the Cairo Geniza. [@Marina2022] [@Zinger2019] #

The smaller second section was broadly related to what is commonly referred to as the “India Book” # which became a collaboration between Goitein and M.A. Friedman which ultimately resulted in the (posthumous) book India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza “India Book” (2007).

The cards were all written in a variety of Hebrew, English, and Arabic based on the needs of the notes and the original languages for the documents with which they deal.

In addition to writing on cards, Goitein also wrote notes on pieces of paper that he happened to have lying around. [@Zinger2019] # Zinger provides an example of this practice and quotes a particular card which also shows some of Goitein’s organizational practice:

In some cases, not unlike his Geniza subjects, Goitein wrote his notes on pieces of paper that were lying around. To give but one example, a small note records the location of the index cards for “India Book: Names of Persons” from ‘ayn to tav: “in red \ or Gray \ box of geographical names etc. second (from above) drawer to the left of my desk 1980

in the left right steel cabinet in the small room 1972” is written on the back of a December 17, 1971, note thanking Goitein for a box of chocolate (roll 11, slide 503, drawer13 [2.1.1], 1191v).

This note provides some indication of some of his arrangements for note taking and how he kept his boxes. They weren’t always necessarily in one location within his office and moved around as indicated by the strikethrough, according to his needs and interests. It also provides some evidence that he revisited and updated his notes over time.

In Zinger’s overview of the documents for the Cairo Geniza, he also provides a two page chart breakdown overview of the smaller portion of Goitein’s 7,000 cards relating to his study of the Geniza with a list of the subjects, subdivisions, microfilm rolls and slide numbers, and the actual card drawer numbers and card numbers. These cards were in drawers 1-15, 17, and 20-22. [@Zinger2019] #

Method

Zinger considers the collection of 27,000 cards “even more impressive when one realizes that both sides of many of the cards have been written on.” [@Zinger2019] Goitein obviously broke the frequent admonishment of many note takers (in both index card and notebook traditions) to “write only on one side” of his cards, slips, or papers. # This admonishment is seen frequently in the literature as part of the overall process of note taking for writing includes the ability to lay cards or slips out on a surface and rearrange them into logical orderings before copying them out into a finished work. One of the earliest versions of this advice can be seen in Konrad Gessner’s Pandectarum Sive Partitionum Universalium (1548).

Zinger doesn’t mention how many of his 27,000 index cards are double-sided, but one might presume that it is a large proportion. # Given that historian Keith Thomas mentions that without knowing the advice he evolved his own practice to only writing on one side [@Thomas2010], it might be interesting to see if Goitein evolved the same practice over his 35 year span of work. #

The double sided nature of many cards indicates that they could have certainly been a much larger collection if broken up into smaller pieces. In general, they don’t have the shorter atomicity of content suggested by some note takers. Goitein seems to have used his cards in a database-like fashion, similar to that expressed by Beatrice Webb [@Webb1926], though in his case his database method doesn’t appear to be as simplified or as atomic as hers. #

Card Index Output

As the ultimate goal of many note taking processes is to create some sort of output, as was certainly the case for Goitein’s work, let’s take a quick look at the result of his academic research career.

S.D. Goitein’s academic output stands at 737 titles based on a revised bibliography compiled by Robert Attal in 2000, which spans 93 pages. [@Attal2000] # # A compiled academia.edu profile of Goitein lists 800 articles and reviews, 68 books, and 3 Festschriften which tracks with Robert Atta’s bibliography. #. Goitein’s biographer Hanan Harif also indicates a total bibliography of around 800 publications. [@NationalLibraryofIsrael2021] #. The careful observer will see that Attal’s list from 2000 doesn’t include the results of S.D. Goitein’s India book work which weren’t published in book form until 2007.

Perhaps foremost within his massive bibliography is his influential and magisterial six volume A Mediterranean Society: The Jewish communities of the Arab World as Portrayed in the Documents of the Cairo Geniza (1967–1993), a six volume series about aspects of Jewish life in the Middle Ages which is comprised of 2,388 pages. # When studying his card collection, one will notice that a large number of cards in the topically arranged or commonplace book-like portion were used in the production of this magnum opus. # Zinger says that they served as the skeleton of the series and indicates as an example:

…in roll 26 we have the index cards for Mediterranean Society, chap. 3, B, 1, “Friendship” and “Informal Cooperation” (slides 375–99, drawer 24 [7D], 431–51), B, 2, “Partnership and Commenda” (slides 400–451, cards 452–83), and so forth. #

Given the rising popularity of the idea of using a zettelkasten (aka slip box or card index) as a personal knowledge management tool, some will certainly want to compare the size of Goitein’s output with that of his rough contemporary German sociologist Niklas Luhmann (1927-1990). Luhmann used his 90,000 slip zettelkasten collection to amass a prolific 550 articles and 50 books. [@Schmidt2016]. Given the disparity in the overall density of cards with respect to physical output between the two researchers one might suspect that a larger proportion of Goitein’s writing was not necessarily to be found within his card index, but the idiosyncrasies of each’s process will certainly be at play. More research on the direct correlation between their index cards and their writing output may reveal more detail about their direct research and writing processes.

Digital Archive

Following his death in February 1985, S.D. Goitein’s papers and materials, including his twenty-six drawer zettelkasten, were donated by his family to the Jewish National and University Library (now the National Library of Israel) in Jerusalem where they can still be accessed. [@Zinger2019] #

In an attempt to continue the work of Goitein’s Geniza lab, Mark R. Cohen and A. L. Udovitch made arrangements for copies of S.D. Goitein’s card index, transcriptions, and photocopies of fragments to be made and kept at Princeton before the originals were sent. This repository then became the kernel of the modern Princeton Geniza Lab. [@PrincetonGenizaLaba] # #

Continuing use as an active database and research resource

The original Princeton collection was compacted down to thirty rolls of microfilm from which digital copies in .pdf format have since been circulating among scholars of the documentary Geniza. [@Zinger2019] #

Goitein’s index cards provided a database not only for his own work, but for those who studied documentary Geniza after him. [@Zinger2019] # S.D. Goitein’s index cards have since been imaged and transcribed and added to the Princeton Geniza Lab as of May 2018. [@Zinger2019] Digital search and an index are also now available as a resource to researchers from anywhere in the word. #

Historically it has generally been the case that repositories of index cards like this have been left behind as “scrap heaps” which have meant little to researchers other than their originator. In Goitein’s case his repository has remained as a beating heart of the humanities-based lab he left behind after his death.

In Geniza studies the general rule of thumb has become to always consult the original of a document when referencing work by other scholars as new translations, understandings, context, history, and conditions regarding the original work of the scholar may have changed or have become better understood.[@Zinger2019] # In the case of the huge swaths of the Geniza that Goitein touched, one can not only reference the original fragments, but they can directly see Goitein’s notes, translations, and his published papers when attempting to rebuild the context and evolve translations.

Posthumous work

Similar to the pattern following Walter Benjamin’s death with The Arcades Project (1999) and Roland Barthes’ Mourning Diary (2010), Goitein’s card index and extant materials were rich enough for posthumous publications. Chief among these is India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza “India Book.” (Brill, 2007) cowritten by Mordechai Friedman, who picked up the torch where Goitein left off. # # However, one must notice that the amount of additional work which was put into Goitein’s extant box of notes and the subsequent product was certainly done on a much grander scale than these two other efforts.

Notes per day comparison to other well-known practitioners

Given the idiosyncrasies of how individuals take their notes, the level of their atomicity, and a variety of other factors including areas of research, other technology available, slip size, handwriting size, etc. comparing people’s note taking output by cards per day can create false impressions and dramatically false equivalencies. This being said, the measure can be an interesting statistic when taken in combination with the totality of these other values. Sadly, the state of the art for these statistics on note taking corpora is woefully deficient, so a rough measure of notes per day will have to serve as an approximate temporary measure of what individuals’ historical practices looked like.

With these caveats firmly in mind, let’s take a look at Goitein’s output of roughly 27,000 cards over the span of a 35 year career: 27,000 cards / [35 years x 365 days/year] gives us a baseline of approximately 2.1 cards per day. #. Restructuring this baseline to single sided cards, as this has been the traditional advice and practice, if we presume that 3/4ths of his cards were double-sided we arrive at a new baseline of 3.7 cards per day.

Gotthard Deutch produced about 70,000 cards over the span of about 17 years giving him an output of about 11 cards per day. [@Lustig2019] #

Niklas Luhmann’s collection was approximately 90,000 cards kept over about 41 years giving him about 6 cards per day. [@Ahrens2017] #

Hans Blumenberg’s zettelkasten had 30,000 notes which he collected over 55 years averages out to 545 notes per year or roughly (presuming he worked every day) 1.5 notes per day. [@Kaube2013] #

Roland Barthes’ fichier boîte spanned about 37 years and at 12,250 cards means that he was producing on average 0.907 cards per day. [@Wilken2010] If we don’t include weekends, then he produced 1.27 cards per day on average. #

Finally, let’s recall again that it’s not how many thoughts one has, but their quality and even more importantly, what one does with them which matter in the long run. # Beyond this it’s interesting to see how influential they may be, how many they reach, and the impact they have on the world. There are so many variables hiding in this process that a fuller analysis of the statistical mechanics of thought with respect to note taking and its ultimate impact are beyond our present purpose.

Further Research

Based on a cursory search, no one seems to have picked up any deep research into Goitein’s card collection as a tool the way Johannes F.K. Schmidt has for Niklas Luhmann’s archive or the Jonathan Edwards Center at Yale has for Jonathan Edwards’ Miscellanies Index.

Goitein wrote My Life as a Scholar in 1970, which may have some methodological clues about his work and method with respect to his card index. He also left his diaries to the National Library of Israel as well and these may also have some additional clues. # Beyond this, it also stands to reason that the researchers who succeeded him, having seen the value of his card index, followed in his footsteps and created their own. What form and shape do those have? Did he specifically train researchers in his lab these same methods? Will Hanan Harif’s forthcoming comprehensive biography of Goitein have additional material and details about his research method which helped to make him so influential in the space of Geniza studies? Then there are hundreds of small details like how many of his cards were written on both sides? # Or how might we compare and contrast his note corpus to others of his time period? Did he, like Roland Barthes or Gotthard Deutch, use his card index for teaching in his earlier years or was it only begun later in his career?

Other potential directions might include the influence of Braudel’s lab and their research materials and methods on Goitein’s own. Surely Braudel would have had a zettelkasten or fichier boîte practice himself?

References

- Attal, Robert. A Bibliography of the Writings of Prof. Shelomo Dov Goitein. Second, Expanded edition. Jerusalem: Ben Zvi Institute, 2000.

- Barthes, Roland. Mourning Diary. Macmillan, 2010. https://us.macmillan.com/books/9780374533113/mourningdiary.

- Bernheim, Ernst. Lehrbuch der historischen Methode und der Geschichtsphilosophie : mit Nachweis der wichtigsten Quellen und Hilfsmittelzum Studium der Geschichte … völlig neu bearbeitete und vermehrte Auflage. 1889. Reprint, Leipzig : Duncker, 1903. http://archive.org/details/lehrbuchderhisto00bernuoft.

- Dershowitz, Nachum, and Ephraim Nissan. Language, Culture, Computation: Computing for the Humanities, Law, and Narratives: Essays Dedicated to Yaacov Choueka on the Occasion of His 75 Birthday, Part II. Springer, 2014.

- Franklin, Arnold E. “Jewish Communal History in Geniza Scholarship: Part 2, Goitein’s Successors.” Jewish History 32, no. 2 (December 1, 2019): 143–59. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-019-09313-7.

- Frenkel, Miriam, and Moshe Yagur. “Jewish Communal History in Geniza Scholarship: Part 1, From Early Beginnings to Goitein’s Magnum Opus.” Jewish History 32, no. 2 (December 1, 2019): 131–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-018-9310-8.

- Gessner, Konrad. Pandectarum Sive Partitionum Universalium. 1st Edition. Zurich: Christoph Froschauer, 1548.

- Goitein, Shelomo Dov, and Mordechai Friedman. India Traders of the Middle Ages: Documents from the Cairo Geniza “India Book.” Brill, 2007. https://brill.com/display/title/11514.

- Kaube, Jürgen. “Zettelkästen: Alles und noch viel mehr: Die gelehrte Registratur.” FAZ.NET, March 6, 2013. https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/geisteswissenschaften/zettelkaesten-alles-und-noch-viel-mehr-die-gelehrte-registratur-12103104.html.

- Langlois, Charles Victor, and Charles Seignobos. Introduction to the Study of History. Translated by George Godfrey Berry. First. New York: Henry Holt and company, 1898. http://archive.org/details/cu31924027810286.

- Lieberman, Phillip I. “Goitein’s Unfinished Legacies.” Jewish History 32, no. 2 (December 1, 2019): 525–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-018-9311-7.

- Lustig, Jason. “‘Mere Chips from His Workshop’: Gotthard Deutsch’s Monumental Card Index of Jewish History.” History of the Human Sciences 32, no. 3 (July 1, 2019): 49–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0952695119830900.

- NLI Treasures – Outstanding Archives: Shlomo Dov Goitein with Dr. Hanan Harif and Matan Barzilai. National Library of Israel, 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WIfH-iSGa5M.

- Princeton Geniza Lab. “Goitein’s Index Cards,” 2022. https://genizalab.princeton.edu/resources/goiteins-index-cards.

- Princeton Geniza Lab. “Goitein and His Lab.” Research Lab. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://genizalab.princeton.edu/about/history-princeton-geniza-lab/goitein-and-his-lab.

- Princeton Geniza Lab. “Text Searchable Database.” Research Lab. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://genizalab.princeton.edu/about/history-princeton-geniza-lab/text-searchable-database.

- Rustow, Marina, and Eve Krakowski, et al. Princeton Geniza Lab. “Goitein’s Index Cards,” 2022. https://genizalab.princeton.edu/resources/goiteins-index-cards.

- Schmidt, Johannes F. K. “Niklas Luhmann’s Card Index: Thinking Tool, Communication Partner, Publication Machine.” In Forgetting Machines: Knowledge Management Evolution in Early Modern Europe, 287–311. Library of the Written Word 53. Brill, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004325258_014.

- Thomas, Keith. “Diary: Working Methods.” London Review of Books, June 10, 2010. https://www.lrb.co.uk/the-paper/v32/n11/keith-thomas/diary.

- Webb, Beatrice Potter. My Apprenticeship. First Edition. New York: Longmans, Green & Co., 1926.

- Zinger, Oded. “Finding a Fragment in a Pile of Geniza: A Practical Guide to Collections, Editions, and Resources.” Jewish History 32, no. 2 (December 1, 2019): 279–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10835-019-09314-6.

Footnotes

- In my preliminary literature search here, I have not found any direct references to indicate that Goitein specifically called his note collection a “Zettekasten”. References to it have remained restricted to English generally as a collection of index cards or a card index.↩︎

- While not directly confirmed (yet), due to the seeming correspondence of the number of cards and their corpus descriptions with respect to the sizes, it’s likely that the 20,000 3 x 5″ cards were his notes covering individual topics while the 7,000 5 x 8″ cards were his notes and descriptions of a single fragment from the Cairo Geniza. #↩︎

🎧 Space, Pixels and Cognition (Yiliu and John) | T4T S01E03

A conversation about spatial computing and the power of operating in a spatial environment with the founder of Softspace, Yiliu Shen-Burke, and John Underkoffler of Oblong Industries.