Feel free to email or call me directly and we can set up a time to chat.

Tag: IndieWeb for Journalism

Some thoughts and questions about online comments

I’ve spent part of the morning going town a rabbit hole on comments on news and media sites and reading a lot of comments from an old episode of On the Media from July 25, 2008. (Here’s the original page and commentary as well as Jeff Jarvis’ subsequent posts[1][2], with some excellent comments, as well as two wonderful posts from Derek Powazek.[3][4])

I’ve spent part of the morning going town a rabbit hole on comments on news and media sites and reading a lot of comments from an old episode of On the Media from July 25, 2008. (Here’s the original page and commentary as well as Jeff Jarvis’ subsequent posts[1][2], with some excellent comments, as well as two wonderful posts from Derek Powazek.[3][4])

Now that we’re 12 years on and have also gone through the social media revolution, I’d give my left arm to hear an extended discussion of what many of the principals of that conversation think today. Can Bob Garfield get Derek Powacek, Jeff Jarvis, Kevin Marks, Jay Rosen, Doc Searls, and Ira Glass back together to discuss where we’re at today?

Maybe we could also add in folks like danah boyd and Shoshana Zuboff for their takes as well?

Hopefully I’m not opening up any old wounds, but looking back at these extended conversations really makes me pine for the “good old days” before social media seemingly “ruined” things.

Why can’t we get back more substantive conversations like these online? Were we worried about the wrong things? Were early unfiltered comments really who we were and just couldn’t see it then? Does social media give us the right to reach in addition to the right to speech? How could we be doing better? Where should we go from here?

You caused a lot of discussion in your OtM piece about comments — and that discussion itself — in the comments on WNYC’s blog, in the comments on mine, and in blogs elsewhere — is an object lesson in the value of the conversation online.

But note well, my friend, that all of these people are speaking to you with intelligence, experience, generosity, and civility. You know what’s missing? Two things: First, the sort of nasty comments your own piece decries. And second: You. ❧

Important!

Annotated on February 25, 2020 at 10:54AM

The comments on this piece are interesting and illuminating, particularly all these years later. ❧

Annotated on February 25, 2020 at 11:07AM

Why can’t there be more sites with solid commentary like this anymore? Do the existence of Twitter and Facebook mean whe can’t have nice things anymore? ❧

Annotated on February 25, 2020 at 11:11AM

There's been a bit of a backlash recently against the angry commenter on newspaper websites. Some are calling for newspapers to stop allowing comments sections all together. But what about democracy on the web? Bob, with the help of "This American Life"'s Ira Glass, ruminates on the dark side of the comments section.

I just wrote a long, considered, friendly, and I hope helpful comment here but — sorry, I have to see the irony in this once again — your system wouldn’t let me say anything longer tahn 1,500 characters. If you want more intelligent conversations, you might want to expand past soundbite. ❧

In 2008, even before Twitter had become a thing at 180 characters, here’s a great reason that people should be posting their commentary on their own blogs.

This example from 2008 is particularly rich as you’ll find examples on this page of Derek Powazek and Jeff Jarvis posting comments with links to much richer content and commentary on their own websites.

We’re a decade+ on and we still haven’t managed to improve on this problem. In fact, we may have actually made it worse.

I’d love to see On the Media revisit this idea. (Of course their site doesn’t have comments at all anymore either.)

Annotated on February 25, 2020 at 10:47AM

The other day Bob Garfield had a good kvetch about dumb comments on newspaper websites on his show, On The Media, and I posted my two cents, but I still don’t feel better. I think that’…

The other day Bob Garfield had a good kvetch about dumb comments on newspaper websites on his show, On The Media, and I posted my two cents, but I still don’t feel better. I think that’s because Bob’s partly right: comments do suck sometimes.

So, instead of just poking him for sounding like Grandpa Simpson, I’d like to help fix the problem. Here are ten things newspapers could do, right now, to improve the quality of the comments on their sites. (There are lots more, but you know how newspaper editors can’t resist a top ten list.)

I love this list which I feel is very solid. I also think that newspapers/magazines could do this with an IndieWeb approach to give themselves even more control over aggregating and guiding their conversations.

Instead of moving in the correct direction of taking more ownership, most journalistic outlets (here’s a recent example) seem to be ceding their power and audience away to social media. Sure people will have conversations about pieces out in the world, but why not curate and encourage a better and more substantive discussion where you actually have full control? Twitter reactions may help spread their ideas and give some reach, but at best–from a commentary perspective–Twitter and others can only provide for online graffiti-like reactions for the hard work.

I particularly like the idea of having an editor of the comment desk.

Simultaneously saving journalism and social media

What if local newspapers/magazines or other traditional local publishers ran/operated/maintained IndieWeb platforms or hubs (similar to micro.blog, Multi-site WordPress installs, or Mastodon instances) to not only publish, aggregate, curate, and disseminate their local area news, but also provided that social media service for their customers?

Reasonable mass hosting can be done for about $2/month which could be bundled in with regular subscription prices of newspapers. This would solve some of the problems that people face with social media presences on services like Facebook and Twitter while simultaneously solving the problem of newspapers and journalistic enterprises owning and managing their own distribution. It would also give a tighter coupling between journalistic enterprises and the communities they serve.

The decentralization of the process here could also serve to prevent the much larger attack surfaces that global systems like Twitter and Facebook represent from being disinformation targets for hostile governments or hate groups. Tighter community involvement could be a side benefit for local discovery, aggregation, and interaction.

Many journalistic groups are already building and/or maintaining their own websites, why not go a half-step further. Additionally many large newspaper conglomerates have recently been building their own custom CMS platforms not only for their own work, but also to sell to other smaller news organizations that may not have the time or technical expertise to manage them.

A similar idea is that of local government doing this sort of building/hosting and Greg McVerry and I have discussed this being done by local libraries. While this is a laudable idea, I think that the alignment of benefits between customers and newspapers as well as the potential competition put into place could be a bigger beneficial benefit to all sides.

Featured photo by AbsolutVision on Unsplash

How to follow the complete output of journalists and other writers?

This is sure to leave journalists wondering how to better serve their own personal brand either when they leave a major publication for which they’ve long held an association (examples: Walt Mossberg leaving The New York Times or Leon Wieseltier leaving The New Republic) or alternatively when they’re just starting out and writing for fifty publications and attempting to build a bigger personal following for their work which appears in many locations (examples include nearly everyone out there).

Increasingly I find myself doing insane things to try to follow the content of writers I love. The required gymnastics are increasingly complex to try to track writers across hundreds of different outlets and dozens of social media sites and other platforms (filtering out unwanted results is particularly irksome). One might think that in our current digital media society, it would be easy to find all the writing output of a professional writer like Ta-nehisi Coates, for example, in one centralized place.

I’m also far from the only one. In fact, I recently came across this :

I wish there was a way to subscribe to writers the same way you can use RSS. Obviously twitter gets you the closest, but usually a whole lot more than just the articles they’ve written. It would be awesome if every time Danny Chau or Wesley Morris published a piece I’d know.

The subsequent conversation in his comments or (a fairly digital savvy crowd) was less than heartening for further ideas.

As Kevin intimates, most writers and journalists are on Twitter because that’s where a lot of the attention is. But sadly Twitter can be a caustic and toxic place for many. It also means sifting through a lot of intermediary tweets to get to the few a week that are the actual work product articles that one wants to read. This also presumes that one’s favorite writer is on Twitter, still using Twitter, or hasn’t left because they feel it’s a time suck or because of abuse, threats, or other issues (examples: Ta-Nehisi Coates, Lindy West, Sherman Alexie).

What does the universe of potential solutions for this problem currently look like?

Potential Solutions

Aggregators

One might think that an aggregation platform like Muck Rack which is trying to get journalists to use their service and touts itself as “The easiest, unlimited way to build your portfolio, grow your following and quantify your impact—for free” might provide journalists the ability to easily import their content via RSS feeds and then provide those same feeds back out so that their readers/fans could subscribe to them easily. How exactly are they delivering on that promise to writers to “grow your following”?!

An illustrative example I’ve found on Muck Rack is Ryan O’Hanlon, a Los Angeles-based writer, who writes for a variety of outlets including The Guardian, The New York Times, ESPN, BuzzFeed, ESPN Deportes, Salon, ESPN Brasil, FiveThirtyEight, The Ringer, and others. As of today they’ve got 410 of his articles archived and linked there. Sadly, there’s no way for a fan of his work to follow him there. Even if the site provided an RSS feed of titles and synopses that forced one to read his work on the original outlet, that would be a big win for readers, for Ryan, and for the outlets he’s writing for–not to mention a big win for Muck Rack and their promise.

I’m sure there have to be a dozen or so other aggregation sites like Muck Rack hiding out there doing something similar, but I’ve yet to find the real tool for which I’m looking. And if that tool exists, it’s poorly distributed and unlikely to help me for 80% of the writers I’m interested in following much less 5%.

Author Controlled Websites

Possibly the best choice for everyone involved would be for writers to have their own websites where they archive their own written work and provide a centralized portfolio for their fans and readers to follow them regardless of where they go or which outlet they’re writing for. They could keep their full pieces privately on the back end, but give titles, names of outlets, photos, and synopses on their sites with links back to the original as traditional blog posts. This pushes the eyeballs towards the outlets that are paying their bills while still allowing their fans to easily follow everything they’re writing. Best of all the writer could own and control it all from soup to nuts.

If I were a journalist doing this on the cheap and didn’t want it to become a timesuck, I’d probably spin up a simple WordPress website and use the excellent and well-documented PressForward project/plugin to completely archive and aggregate my published work, but use their awesome forwarding functionality so that those visiting the URLs of the individual pieces would be automatically redirected to the original outlet. This is a great benefit for writers many of whom know the pain of having written for outlets that have gone out of business, been bought out, or even completely disappeared from the web.

Of course, from a website, it’s relatively easy to automatically cross-post your work to any number of other social platforms to notify the masses if necessary, but at least there is one canonical and centralized place to find a writer’s proverbial “meat and potatoes”. If you’re not doing something like this at a minimum, you’re just making it hard for your fans and failing at the very basics of building your own brand, which in part is to get even more readers. (Hint, the more readers and fans you’ve got, the more eyeballs you bring to the outlets you’re writing for, and in a market economy built on clicks, more eyeballs means more traffic, which means more money in the writer’s pocket. Since a portion of the web traffic would be going through an author’s website, they’ll have at least a proportional idea of how many eyeballs they’re pushing.)

I can’t help but point out that even some who have set up their own websites aren’t quite doing any of this right or even well. We can look back at Ryan O’Hanlon above with a website at https://www.ryanwohanlon.com/. Sadly he’s obviously let the domain registration lapse, and it has been taken over by a company selling shoes. We can compare this with the slight step up that Mssr. Coates has made by not only owning his own domain and having an informative website featuring his books, but alas there’s not even a link to his work for The Atlantic or any other writing anywhere else. Devastatingly his RSS feed isn’t linked, but if you manage to find it on his website, you’ll be less-than-enthralled by three posts of Lorem ipsum from 2017. Ugh! What has the world devolved to? (I can only suspect that his website is run by his publisher who cares about the book revenue and can’t be bothered to update his homepage with events that are now long past.)

Examples of some journalists/writers who are doing some interesting work, experimentation, or making an effort in this area include: Richard MacManus, Marina Gerner, Dan Gillmor, Jay Rosen, Bill Bennett, Jeff Jarvis, Aram Zucker-Scharff, and Tim Harford.

One of my favorite examples is John Naughton who writes a regular column for the Guardian. He has his own site where he posts links, quotes, what he’s reading, his commentary, and quotes of his long form writing elsewhere along with links to full pieces on those sites. I have no problem following some or all of his output there since his (WordPress-based) site has individual feeds for either small portions or all of it. (I’ve also written a short case study on Ms. Gerner’s site in the past as well.)

Newsletters

Before anyone says, “What about their newsletters?” I’ll admit that both O’Hanlon and Coates both have newsletters, but what’s to guarantee that they’re doing a better job of pushing all of their content though those outlets? Most of my experience with newsletters would indicate that’s definitely not the case with most writers, and again, not all writers are going to have newsletters, which seem to be the flavor-of-the month in terms of media distribution. What are we to do when newsletters are passé in 6 months? (If you don’t believe me, just recall the parable of all the magazines and writers that moved from their own websites or Tumblr to Medium.com.)

Tangential projects

I’m aware of some one-off tools that come close to the sort of notifications of writers’ work that might be leveraged or modified into a bigger tool or stand alone platform. Still, most of these are simple uni-taskers and only fix small portions of the overall problem.

Extra Extra

Vishnu Rajan, Andréa López, and friends (hopefully I’m crediting them properly based on what I can find on Twitter) have the project Extra Extra, which is a series of Twitter bots that send updates when one of a handful of journalists either publish or update their articles. An example with some code on Github is the Twitter bot maggietime that tweets every time Maggie Haberman of The New York Times has a new article and another bot Maggie *DIFFS* that tweets when her articles are updated or changed. See also, the related NewsDiffs project.

Savemy.News

Ben Walsh of the Los Angeles Times Data Desk has created a simple web interface at www.SaveMy.News that journalists can use to quickly archive their stories to the Internet Archive and WebCite. One can log into the service via Twitter and later download a .csv file with a running list of all their works with links to the archived copies. Adding on some functionality to add feeds and make them discoverable to a tool like this could be a boon.

Granary

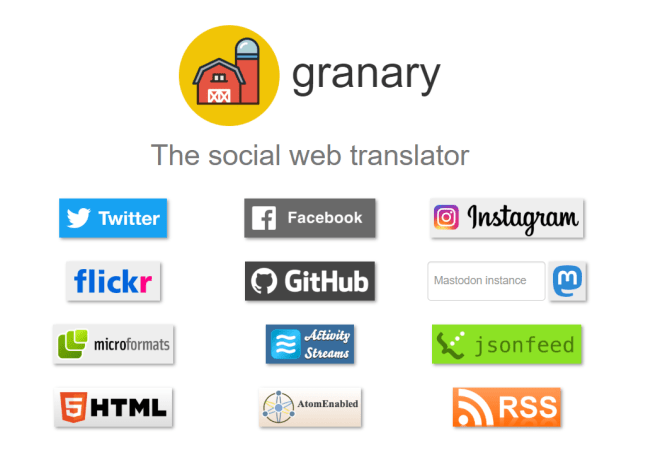

Ryan Barrett has a fantastic open source tool called Granary that “Fetches and converts data between social networks, HTML and JSON with microformats2, ActivityStreams 1 and 2, Atom, RSS, JSON Feed, and more.” This could be a solid piece of a bigger process that pulls from multiple sources, converts them into a common format, and outputs them in a single subscribe-able location.

SubToMe

A big problem that has pushed us away from RSS and other formatted feed readers is providing an easy method of subscribing to content. Want to follow someone on Twitter? Just click a button and go. Wishing it were similar for a variety of feed types, Julien Genestoux‘s SubToMe has created a universal follow button that allows a one-click subscription option (with lots of flexibility and even bookmarklets) for following content feeds on the open web.

Others?

Have you seen any other writers/technologists who have solved this problem? Are there aggregation platforms that solve the problem in reverse? Small pieces that could be loosely joined into a better solution? What else am I missing?

How can we encourage more writers to take this work into their own hands to provide a cleaner solution for their audiences? Isn’t it in their own best interest to help their readers find their work?

I’ve curated portions of a journalism page on IndieWeb wiki to include some useful examples, pointers, and resources that may help in solving portions of this problem. Other ideas and solutions are most welcome!

Digital journalism and online culture.

I wonder how IndieWeb specific his version of journalism is?

👓 Should the Media Quit Facebook? — The Disinformation War | Columbia Journalism Review

With all that has transpired between Facebook and the media industry over the past couple of years—the repeated algorithm changes, the head fakes about switching to video, the siphoning off of a significant chunk of the industry’s advertising revenue—most publishers approach the giant social network with skepticism, if not outright hostility. And yet, the vast majority of them continue to partner with Facebook, to distribute their content on its platform, and even accept funding and resources from it.

Personally I feel like newspapers, magazines, and media should help to be providing IndieWeb-based open platforms of their own for not only publishing their own work, but for creating the local commons for their readers and constituents to be able to freely and openly interact with them.

They’re letting Facebook and other social media to own too much of their content and even their audience. Building tools to take it back could help them, their readers, and even democracy out all at the same time.

Sadly, based on what I’m seeing here, however, even CJR has outsourced their platform for this series to SquareSpace. At least they’re publishing it on a URL they own and control.

👓 Scroll is acquiring Nuzzel | Scroll Blog

A note from Tony Haile, CEO of Scroll

TL;DR

- Scroll is acquiring Nuzzel

- The core service isn’t going to change beyond removing the ads

- We’re spinning out the media intelligence business

We need more competition in the space of “discovery” on the web and particularly in the area of allowing users to control the levers that go into some of that discovery. The blackbox algorithms of the social media giants certainly can’t be trusted because of their financial motivations. In some sense, I view Nuzzel as a real-time directory, but one whose cache is flushed at regular intervals instead of saving all the data for a later date and time or other additional searching. I wonder what a engine like Nuzzel would look like if it kept all the data and allowed itself to be searchable in a long-tail way?

👓 Do You Still Have A Job At BuzzFeed? | BuzzFeed

"As you know, the company is going thru a reorganization..."

The odd part was that in terms of presentation I didn’t realize until almost the end that this wasn’t a primary part of BuzzFeed, but rather their “Community” section. While it’s nice that they give readers a place like this to contribute free content which only goes towards their own clicks for advertising, it would be far more interesting and useful if they were letting their community use their platform to host their own content on their own domains instead, and then allowing them to either pay for it directly or using advertising against it to cover the tab. This would be the sort of hybrid social media and journalism idea I’ve touched on in the past. Instead, this effort and those of others like the Huffington Post seem to be wholly benefiting the outlet more than they do the individual. The pendulum needs to swing back the other way soon.

👓 Journalism is the conversation. The conversation is journalism. | Jeff Jarvis

I am sorely disappointed in The New York Times’ Farhad Manjoo, CNN’s Brian Stelter, and other journalists who these days are announcing to…

Here yet again, I can’t help but think that journalistic outlets ought to be using their platforms and their privilege and extend them to their audiences as a social media platform of sorts. This could kill the siren song of the toxic platforms and simultaneously bring the journalists and the public into a more direct desperate congress. There is nothing stopping CNN or The New York Times from building an open version of Twitter, Facebook, Tumblr, or even blogging platform on which everyone could participate. In fact, there are already several news outlets that have gotten into the content management system business and are selling their wares to other newspapers and magazines. Why not go a half-step further and allow the public to use them as well? The IndieWeb model for this seems like an interesting one which could dramatically benefit both sides and even give journalism another useful revenue stream.

Perhaps Kinja wasn’t a bad idea for a CMS cum commenting system, it just wasn’t open web enough?