Undergraduate and graduate classes will continue online, students are encouraged not to return to campus after spring break

Reads, Listens

Playlist of posts listened to, or scrobbled

This is how we all help slow the spread of coronavirus.

Do you remember the scene of Web Apocalypse Not Now where Lieutenant Colonel Bill Feedmore boasts, “I love the smell of an RSS feed in the morning!” I hope not. But tinkering with RSS n…

Only an actor of extraordinary versatility and emotional depth such as Max von Sydow could have played Jesus, Father Merrin and Ming the Merciless.

Forks can speed up eating. Historically, however, Ann Wroe says their role has been to slow things down.

plangent ❧

Annotated on March 09, 2020 at 10:59PM

I just pushed the first set of improvements to Parse This to support JSON-LD. Parse This takes an incoming URL and converts it to mf2 or jf2. It is used by Post Kinds and by Yarns Microsub to handle this. So, assuming the default arguments are set, the parser will, for a URL that is not a feed...

Last year, the California Attorney General held a tense press conference at a tiny elementary school in the one working class, black neighborhood of the mostly wealthy and white Marin County. His office had concluded that the local district "knowingly and intentionally" maintained a segregated school, violating the 14th amendment. He ordered them to fix it, but for local officials and families, the path forward remains unclear, as is the question: what does "equal protection" mean?

- Eric Foner is author of The Second Founding

Hosted by Kai Wright. Reported by Marianne McCune.

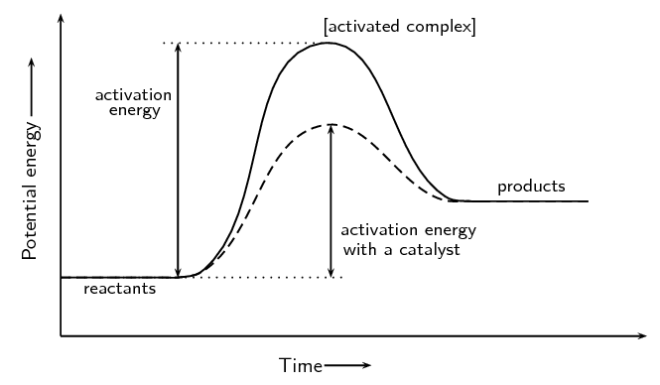

I’m reminded of endothermic chemical reactions that take a reasonably high activation energy (an input cost), but one that is worth it in the end because it raises the level of all the participants to a better and higher level in the end. When are we going to realize that doing a little bit of hard work today will help us all out in the longer run? I’m hopeful that shows like this can act as a catalyst to lower the amount of energy that gets us all to a better place.

This Marin county example is interesting because it is so small and involves two schools. The real trouble comes in larger communities like Pasadena, where I live, which have much larger populations where the public schools are suffering while the dozens and dozens of private schools do far better. Most people probably don’t realize it, but we’re still suffering from the heavy effects of racism and busing from the early 1970’s.

All this makes me wonder if we could apply some math (topology and statistical mechanics perhaps) to these situations to calculate a measure of equity and equality for individual areas to find a maximum of some sort that would satisfy John Rawls’ veil of ignorance in better designing and planning our communities. Perhaps the difficulty may be in doing so for more broad and dense areas that have been financially gerrymandered for generations by redlining and other problems.

I can only think about how we’re killing ourselves as individuals and as a nation. The problem seems like individual choices for smoking and our long term health care outcomes or for individual consumption and its broader effects on global warming. We’re ignoring the global maximums we could be achieving (where everyone everywhere has improved lives) in the search for personal local maximums. Most of these things are not zero sum games, but sadly we feel like they must be and actively work against both our own and our collective best interests.

Piketty’s latest book, “Capital and Ideology,” takes a global overview to inequality and other pressing economic issues of our time.

To have, but maybe not to read. Like Stephen Hawking’s “A Brief History of Time,” “Capital in the Twenty-First Century” seems to have been an “event” book that many buyers didn’t stick with; an analysis of Kindle highlights suggested that the typical reader got through only around 26 of its 700 pages. Still, Piketty was undaunted. ❧

Interesting use of digital highlights–determining how “read” a particular book is.

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 06:02PM

Piketty, however, sees inequality as a social phenomenon, driven by human institutions. Institutional change, in turn, reflects the ideology that dominates society: “Inequality is neither economic nor technological; it is ideological and political.” ❧

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 06:06PM

I was struck, for example, by his extensive discussion of the evolution of slavery and serfdom, which made no mention of the classic work of Evsey Domar of M.I.T., who argued that the more or less simultaneous rise of serfdom in Russia and slavery in the New World were driven by the opening of new land, which made labor scarce and would have led to rising wages in the absence of coercion. ❧

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 06:10PM

For Piketty, rising inequality is at root a political phenomenon. The social-democratic framework that made Western societies relatively equal for a couple of generations after World War II, he argues, was dismantled, not out of necessity, but because of the rise of a “neo-proprietarian” ideology. Indeed, this is a view shared by many, though not all, economists. These days, attributing inequality mainly to the ineluctable forces of technology and globalization is out of fashion, and there is much more emphasis on factors like the decline of unions, which has a lot to do with political decisions. ❧

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 06:11PM

For the past ten years, I have written a lengthy year-end series, documenting some of the dominant narratives and trends in education technology. I think it is worthwhile, as the decade draws to a close, to review those stories and to see how much (or how little) things have changed. You can read the series here: 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019.

I thought for a good long while about how best to summarize this decade, and inspired by the folks at The Verge, who published a list of “The 84 biggest flops, fails, and dead dreams of the decade in tech,” I decided to do something similar: chronicle for you a decade of ed-tech failures and fuck-ups and flawed ideas.

I started reading this over the holidays when Audrey released it. It took me four sittings to make it all the way through (in great part because it’s so depressing). I’ve finally picked it back up today to wallow through the last twenty on the list.

I’m hoping that at least a few people pick up the thread she’s always trying to show us and figure out a better way forward. The information theorist in me says that every student has only so much bandwidth and there’s an analogy to the Shannon Limit for how much information one can cram into a person. I’ve been a fan of Cesar Hidalgo’s idea of a personbyte (a word for the limit of information one can put into a person) and the fact that people need to collaborate to produce things bigger and greater than themselves. What is it going to take to get everyone else to understand?

If anything, the only way I suspect we’ll be able to better teach and have students retain information is to use some of the most ancient memory techniques from indigenous cultures rather than technologizing our way out of the perceived problem.

Annotations/Highlights

(only a small portion since HackedEducation doesn’t fit into my usual workflow)

In his review of Nick Srnicek’s book Platform Capitalism, John Hermann writes,

Platforms are, in a sense, capitalism distilled to its essence. They are proudly experimental and maximally consequential, prone to creating externalities and especially disinclined to address or even acknowledge what happens beyond their rising walls. And accordingly, platforms are the underlying trend that ties together popular narratives about technology and the economy in general. Platforms provide the substructure for the “gig economy” and the “sharing economy”; they’re the economic engine of social media; they’re the architecture of the “attention economy” and the inspiration for claims about the “end of ownership.”

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 02:35PM

It isn’t just the use of student data to fuel Google’s business that’s a problem; it’s the use of teachers as marketers and testers. “It’s a private company very creatively using public resources — in this instance, teachers’ time and expertise — to build new markets at low cost,” UCLA professor Patricia Burch told The New York Times in 2017 as part of its lengthy investigation into “How Google Took Over the Classroom.”

Annotated on March 08, 2020 at 03:04PM

So this year I took a systems design approach to the problem. Why wasn’t I doing the things I wanted to do? At first glance, it looked like a simple matter of spending too much time online.

I was, but a lot of my goals, like re-building my website or blogging again, were dependent on the Internet. So instead, I started observing the situations I would find myself in when I self-sabotaged at home and at work, and they all had too much content. Quality content by most people’s standards, but trivial, nonetheless. They were all click-holes. From there I looked at the interaction models and behaviors encouraged by those sites or platforms, and decided to experiment with removing all triggers, digitial or otherwise. The idea was that by “controlling” for these variables, perhaps I would see some sort of change at the end that would give me the space to do the things I really wanted to do and get shit done.

And so The Year of Intentional Internet began.

After reading just a few posts by Desirée García, I’d like to nominate her to give a keynote at the upcoming IndieWeb Summit in June. I totally want to hear her give a talk on The Year of Intentional Internet.

Last year I wrote a thing on Automattic’s design blog about something I keep noodling on, which ultimately boils down to what makes us creative. What gets us to build a website? What the hell is a website today?

I don’t mean “Us” the web community, or tech industry. I mean “Us” as Humankind.

Silly me, I didn’t manage to keep a reference for where I found this article in the first place.

But it is important and has some interesting philosophical questions for the IndieWeb and, for lack of a better framing, future generations of the IndieWeb.

While I have the sort of love and excitement for the web that she talks about, I wonder if others will too?

The other side of me says that one of the great benefits of what the IndieWeb is doing is breaking down all of the larger and complicated pieces of a website down into smaller and simpler component parts. This allows a broader range of people to see and understand them and then potentially remix them into tools that will not only work for them on a day-to-day basis, but to create new and exciting things out of them. I feel like we’re getting closer to this sort of utopia, but even as I see the pieces getting simpler, I also see large projects like WordPress becoming even more difficult and complex to navigate. There is a broader divide between the general public and the professional web developer and not as many people like me who know just enough of both to be dangerous, creative, and yet still productive.

I hope we can continue to break things down to make them easier for everyone to not only use, but to create new and inspiring things.

The paper's series on slavery made avoidable mistakes. But the attacks from its critics are much more dangerous.

Beginning in the last quarter of the 20th century, historians like Gary Nash, Ira Berlin and Alfred Young built on the earlier work of Carter G. Woodson, Benjamin Quarles, John Hope Franklin and others, writing histories of the Colonial and Revolutionary eras that included African Americans, slavery and race. A standout from this time is Edmund Morgan’s American Slavery, American Freedom, which addresses explicitly how the intertwined histories of Native American, African American and English residents of Virginia are foundational to understanding the ideas of freedom we still struggle with today. ❧

These could be interesting to read.

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 09:12PM

Scholars like Annette Gordon-Reed and Woody Holton have given us a deeper understanding of the ways in which leaders like Thomas Jefferson committed to new ideas of freedom even as they continued to be deeply committed to slavery. ❧

I’ve not seen any research that relates the Renaissance ideas of the Great Chain of Being moving into this new era of supposed freedom. In some sense I’m seeing the richest elite whites trying to maintain their own place in a larger hierarchy rather than stronger beliefs in equality and hard work.

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 09:22PM

The green dot is February 29, the date of the South Carolina primary. Biden had gained a point or two before that, but he only really started to skyrocket shortly after the primary. So it’s safe to say that his big victory in South Carolina was the proximate cause of his early March takeoff. But what was responsible for Biden’s South Carolina win in the first place?

Biden went up a lot more, but he was taking votes away from Steyer, Warren, Buttigieg, and Klobuchar.

For now, the debate still seems the most likely cause. That’s a little unusual, since conventional wisdom says that debates don’t move public opinion much, but maybe this was an exception. ❧

Perhaps it was more the fact that the electorate just didn’t know or trust the Steyer, Buttigieg, and Klobuchar centrist crowd enough to vote for them with time running out. As a result the old tried-and-true guy you know pulls in all the people. He didn’t really need an inciting incident other than the looming election. Following the debate without anything else to use to make a decision on, the choice was *fait accompli*.

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:57PM

Who did you last trust with some really personal information?

Small says there are three reasons we might avoid those closest to us when we are grappling with problems about our health, relationships, work, or kids. ❧

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:39PM

The first is that our closest relationships are our most complex ones. ❧

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:39PM

The second reason is that when we are dealing with something difficult, we commonly prefer to confide in people who have been through what we are going through rather than those who know us, seeking “cognitive empathy” over guaranteed warmth or closeness. ❧

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:40PM

The third reason is that in our moment of vulnerability, our need to talk is greater than our need to self-protect. ❧

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:41PM

Adam Smith, writing in 1790, said we can only expect real sympathy from real friends, not from mere acquaintances. More recently, in 1973, Stanford sociologist Mark Granovetter established as a bedrock of social network analysis the idea that we rely on “strong” ties (our inner circle) for support and weak ties (our acquaintances) for information. ❧

Annotated on March 07, 2020 at 08:43PM